Quality

What a rogue architect can teach us about leadership.

Feelings

The other day I was looking through a coffee table book with my young sons that had hundreds of pictures of Boston, MA. The book had amazing pictures of old drawings of the city, pictures of row houses, landscape views of the city, and great pictures of some of Boston’s most iconic buildings. My youngest son, who is not yet four years old, was particularly excited. I would show him a picture of Faneuil Hall, and he’d say, “wow! I like that!” Then I showed him a picture of the old State House and he said excitedly, “that’s so nice!” On and on we’d look at the old buildings which were built for function and tied the city together, and he marveled at each one. After a few minutes of looking at the old buildings, I flipped to the newer pictures and, very careful not to influence him, I showed him a picture of Boston City Hall. He recoiled immediately and was visibly upset as he said, “I DO. NOT. like that!”

It’s not that my son is well-schooled in architecture - he is still learning how to count. You don’t have to have a degree in architecture to know when a building contains The Quality Without a Name. This quality, according to Alexander, can only be felt. My toddler is learning how to think, but what he is very good at, as most toddlers are, is feeling. So when he sees a building as hideous as Boston City Hall, he knows that it’s ugly because he feels that it’s ugly, he doesn’t have to know or think anything else.

But, according to Alexander, The Quality Without a Name is objective and universal, it’s not a matter of taste. Several times throughout the book, Alexander gives examples of when he was working with someone who thought they had a feeling about how something in the building project should be done, but Alexander knew that the feeling was wrong. It was too shallow, it was simply a response, and it wasn’t a considered feeling. When he knew it was wrong he would press them to focus, concentrate, and think about their feelings, to feel their feelings. When the person took the time to do that, they would come to the correct conclusion about the design.

Yes, you can argue that Alexander simply had good taste himself and would pressure people into doing things his way, but he didn’t pressure my kiddo into knowing that Boston City Hall is ugly. And it is ugly. There is no denying that. Say what you will, there is something universal about the Quality Without a Name.

…Commanders run on them

When I was a commander, I constantly told my junior officers, “Gentlemen, commanders run on feelings. The way you make me feel about your plan is what I am going to think about your plan." Now, obviously, I would try to go deeper than just feelings. But for the most part, leaders do run on feelings, and their feelings can have huge impacts on the people they lead. There is an old joke that if the Sergeant Major of the Army has a bad Monday, the lowest private will have a really bad Tuesday. Feelings can be infectious, which is why it is very important to be aware of them, to focus on them, to hone them, to train them. Psychologists actually have a name for this called “critical feeling.”

We often talk about “critical thinking” in the Army. At most of the Army schools that I’ve attended, I’ve been told that I will be taught how to think critically. We tend to approach military problems like we are engineers. X is a problem. Y causes X. If we do Z, Y will go away. If Y goes away, X will no longer be a problem. Therefore, we must do Z. To do Z we need resources A, B, and C. To get those resources we need to accomplish tasks P and Q. Team 1, you will accomplish P and Q. Team 2, once those are complete, you will acquire the resources and transfer them to Team 3. Team 3, you will take resources A, B, and C and do Z. Problem solved. Problem staying solved.

Yes, a lot of problems can be solved this way. But there are many problems that can’t. Can you fix the Army’s suicide problem like this? We’ve lost 4 x as many soldiers to suicide than combat during the Global War on Terror. If we could solve the suicide problem by using linear prooblem solving models, then why does it get worse every year? Can you fix the Army’s recruiting problem like this? Despite standing up an entire functional area for Marketing Officers, recruiting numbers continue to decline. Can you fix a unit’s morale problem with this type of approach to problem-solving? If you could, then why doesn’t everyone do it? Can we fix the military’s sexual assault problem like this? Certainly not.

No, these problems are complex, and complex problems cannot be solved through this linear way of looking at the world. No amount of critical thinking will get you to the correct answer on how to deal with Army suicides, sexual assault, or any complex problem. In fact, most problems cannot be fixed by solutions arrived at through critical thinking. And yet, we treat critical thinking as if it were a teachable skill like marksmanship. Yes, we treat it like the Holy Grail of officership and we completely ignore critical feeling. We may get a few classes or PowerPoint presentations on the importance of empathy, or the value of EQ (emotional intelligence), but we don’t really value those things as an organization. And we certainly do not connect critical feeling with problem-solving.

But what if critical feeling is more important to problem-solving and leadership than critical thinking? What if critical thinking causes more harm than good?

Signage

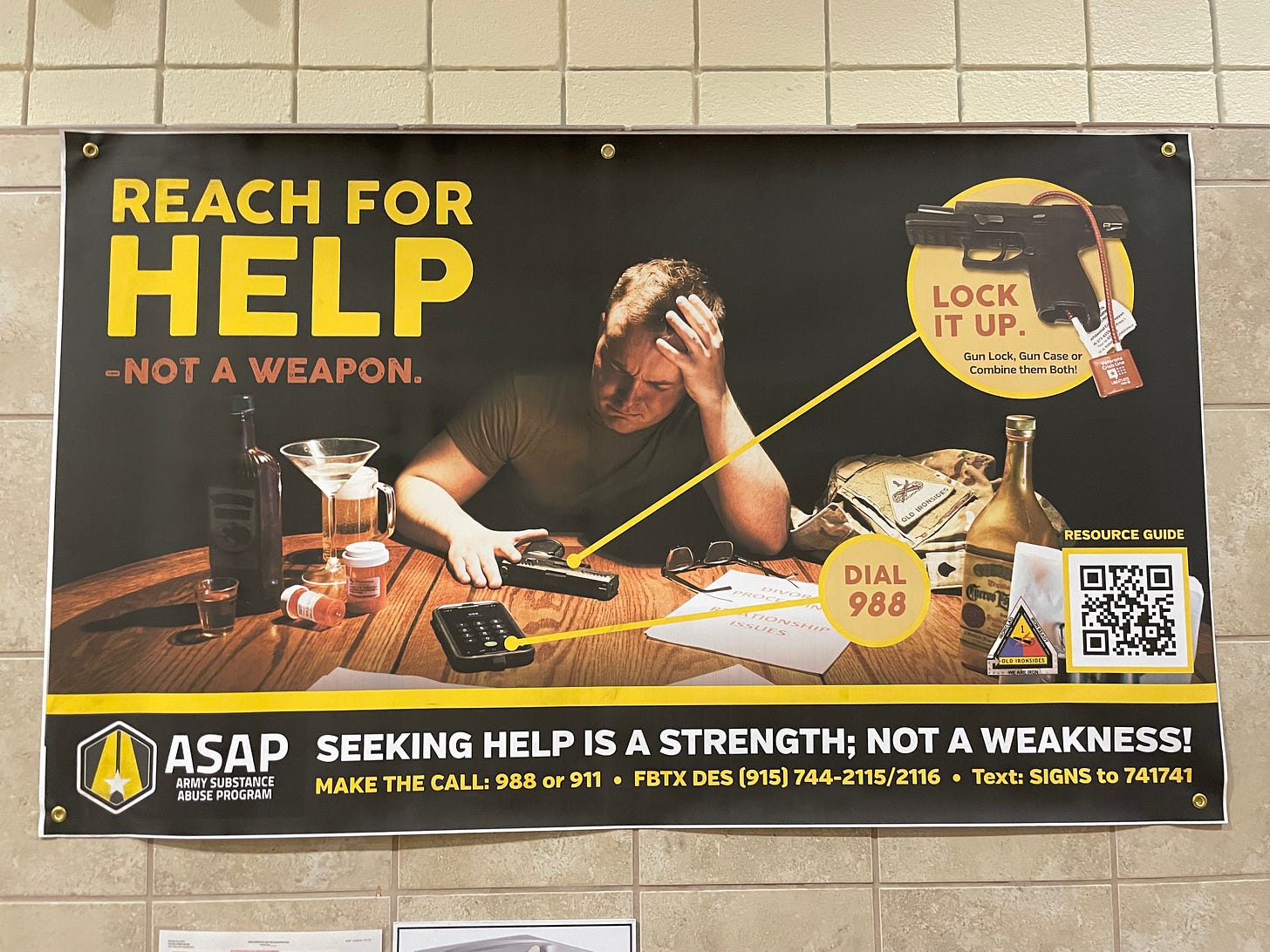

I can see that a lot of critical thinking has been done when I see signs hanging around Army bases. Here’s a giant sign hanging up at the entrance to one of the main gyms:

This poster is very logical:

Soldiers kill themselves with guns.

If the gun is locked, it will present a barrier to the Soldier killing him/herself.

If Soldiers all lock up their guns, suicide will decrease.

Therefore, we should encourage Soldiers to lock up their guns

Furthermore, Soldiers are afraid that seeking help is a sign of weakness.

Let’s say that seeking help is a sign of strength. Because, you know, if we say it then they’ll know.

Yes, lots of critical thinking has gone into this poster.

Here’s the problem: what do you feel when you look at this poster? Do you feel happy? Do you feel excited to come to work? Do you feel like your friends care about you?

NO!

This poster screams: YOU ARE IN A PLACE WHERE THE PEOPLE AROUND YOU DRINK ALCOHOL LIKE JOHN BELUSHI AND GOBBLE PILLS LIKE HUNGY-HUNGRY HIPPOS WHILE THINKING ABOUT HOW WONDERFUL IT WOULD BE IF THE PAIN JUST STOPPED.

It doesn’t take that much critical feeling to know that this poster will do no good.

Just to be clear, I don’t think this sign has caused anyone to kill themselves. But, my goodness, it sure as hell isn’t helping.

Why it isn’t helping is easily explained by some basic psychology.

I was extremely lucky that I read Thinking Fast and Slow before I took command because it helped inform a lot of my decision-making. Over the years it has come to lights that a lot of what is in that book is wrong, and I have come to really appreciate the work of Gerd Gigerenzer, but I will always be thankful for Thinking Fast and Slow and I reference it often.

One of my favorite parts is when he talks about the “Florida Effect.”

In an experiment that became an instant classic, the psychologist John Bargh and his collaborators asked students at New York University most aged eighteen to twenty-two-to assemble four-word sentences from a set of five words (for example, "finds he it yellow instantly"). For one group of students, half the scrambled sentences contained words associated with the elderly, such as Florida, forgetful, bald, gray, or wrinkle. When they had completed that task, the young participants were sent out to do another experiment in an office down the hall.

That short walk was what the experiment was about. The researchers unobtrusively measured the time it took people to get from one end of the corridor to the other. As Bargh had predicted, the young people who had fashioned a sentence from words with an elderly theme walked down the hallway significantly more slowly than the others.1

One of the major problems with Thinking Fast and Slow is that a lot of the studies it references turned out to be victims of the replication crisis. In other words, when other researchers tried to replicate the studies, they didn’t always get the same results. This means that a lot of the results were invalid. If you were taken in by the book Mindset by Carol Dweck, approximately zero of her studies passed replication scrutiny. Her entire book is, in my opinion, bogus.

But I digress.

I am not sure if the Florida Effect has passed any replication attempts, but when I was a commander it at least got me thinking about how I should try to structure the environment for my soldiers.

On my first day in command, I saw a poster hanging on the company bulletin board that listed all of the recent infractions by Soldiers around the brigade and how they had been punished. It said things like:

A Private was charged with lying to an officer and given 2 weeks of extra duty

A Staff Sergeant was charged for fraternizing with lower-enlisted Soldiers and demoted to Sergeant.

A Specialist was charged with being drunk on duty and was demoted to Private.

I tore the poster down because it didn’t feel right to me. I wasn’t thinking about it, but I knew that the poster was bad because I could feel that the poster was bad. It didn’t belong in the same place as my Soldiers. Perhaps it would have fit a different context and should have been hung up somewhere else, like a prosecutor’s office, but it didn’t fit at my company.

What that poster said to me was “You are in a unit where people do bad things. That wasn’t the message I wanted to send.

A few days later the Brigade paralegal came down with new posters showing the most recent convictions and punishments. He asked me where the old sign was and asked where he should hang the new sign. I told him that he would not hang up that sign in my company area. He protested saying, “Sir! It’s in the regulation that it must be posted!” To which I replied, “I don’t care what the regulation says. That poster isn’t going up anywhere near my Soldiers.”

Now, me preventing that poster from being hung up wasn’t the cause of any of the positive results that we achieved. But it was the thousands or tens of thousands of decisions like that which we made on a daily basis that helped us build a unit that contained the Quality Without a Name. Some of those decisions required critical thinking and many of them required critical feeling.

How does one create a team or an organization that contains The Quality Without a Name? No team is perfect, it never can be. But it is obvious when you are in a group that functions well and blatantly obvious when you are in a group that functions poorly. There are many characteristics of high-performing teams, but none of those characteristics fully capture just how good a team is. Many teams operate just fine on a daily routine basis, but whether or not that team contains The Quality Without a Name requires that team to perform at the same level or higher during times of extreme stress. Without that stress, you can never really know the true strength of that team

Process

One of the reasons we rely on critical thinking, and ignore critical feeling, is that critcial thinking is much, much easier. Critical thinking is linear. It is easy to follow the logic of critical thinking from identifying the problem all the way through to finding possible solutions and then choosing the best one. Critical feeling, on the other hand, is much messier. There is no linear line of reasoning to follow. In critical feeling, solutions and ideas emerge, they aren’t listed and arrived at through reasoning.

Have you ever watched videos of Taylor Swift writing songs?(Click) If you haven’t, you should. How much critical thinking is Taylor using as she writes these songs? Zero. She can feel what sounds good. She tries out multiple things until she finds the way to sing the song that is objectively correct. And as you watch her, you too can hear that she finds the way to sing the song correctly. Taylor writes music that contains the Quality Without a Name. Not all of her music finds that quality2, but much of it does. This quality emerges in her music through a complex interaction between her, her writing partner, and the multiple instruments and playbacks. It isn’t planned in advance through a system of research and goal setting.

And so it is with The Quality Without a Name - it emerges through the interactions of multiple players and variables.

Going back to architecture, according to Alexander, The Quality Without a Name is a result of the process of building a building, it’s not something that can be planned into the actual physical structure of the building itself. Alexander, who sadly passed away a few months ago, was completely opposed to the modern way of building, where architects make drawings of buildings they won’t live or work in, and then hand the drawings to builders who build them as cheaply as possible. You cannot achieve The Quality Without a Name through this method.

Alexander was appalled by the modern architecture that was proliferating around him. He chaffed at the arrogance of central urban planning. He wanted to build differently. Rather than create nice-looking drawings and then intimidate his customers with his expertise, he took his customers to the site where the building project was to be done and had them walk around. While they walked around the site, he would ask questions and let them do the imagining and help them develop their own vision. He would ask penetrating questions about how they felt about certain things. He would gather specific information about their desires and daily routines. Together they would place flags to mark where the walls and rooms should be and make chalk marks for where paths or benches would go. If any drawing was done, they were rough sketches to get an idea, never meant to be exact representations. He would spend all day with them watching the sun to see how light cast itself on the site.

This was the opposite of central planning. It was the opposite of the brilliant architect working in isolation. Alexander wasn’t trying to impress other architects, he was trying to build beauty into the world. This was Alexander facilitating a process of emergence in which a building came into being in harmony with its surroundings, through the vision of those who were actually going to use it. After several weeks of visiting the site and thinking and reflecting, a builder would be hired. Alexander and his customer would then work with a builder to make the vision a reality.

Frequent readers of this newsletter will immediately recognize that The Stakeholder Planning Process, is Alexander’s exact same idea applied in a military context. I was shocked to discover the similarities! I followed this process when I planned my company CALFX, which I wrote about in “Network.” I also laid out how you could follow this process to fix administrative systems in “Laziness Part 2.”

As an aside, I won’t go into detail about Alexander’s Pattern Languages and how important they are for his process, but I’ll say that the military already has a pretty good language that is almost like a Pattern Language for conflict. It is a little incomplete, but it’s not half bad. I leave this discussion for a future essay.

So, when it comes to building a team and fulfilling the team’s mission, The Quality Without a Name emerges comes from a process of interactions among the people on the team.

It is the leader’s job, then, to manage that interaction, not to impose it; to tease it out, not to force it through; to set the conditions for it to arise naturally; not to order it into existence by fiat. If you remember in a previous essay I quoted Lao Tzu who said,

The best of all rulers is but a shadowy presence to his subjects.

Next comes the ruler they love and praise;

Next comes to one they fear;

Next comes the one with whom they take liberties.

When there is not enough faith, there is a lack of good faith.

Hesitant, he does not utter words lightly

When his task is accomplished and his work done

The people all say, ‘It happened to us naturally.’

Operationalize

Now I know what you’re thinking:

“Bro, I’m in the infantry. If I stand in front of my boss and say some woo-woo sh*t like, ‘our plan emerged through a self-organizing process of discovery and intense collaboration where we explored our feelings and intuitions about our unique operating environment and how best to achieve our objectives,’ I’ll be lucky to be assigned as the Officer-In-Charge of a landscaping detail.”

Your fears, “bro,” are not incorrect. Military planning does follow a fairly rigid linear process that is codified in doctrine and refined through a unit’s written Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). And yes, you deviate at your peril.

But why would you ever need to say that statement above to your commander?

In the end, commanders need to show results. It may seem counter-intuitive, but using a (mostly) unstructured collaborative planning process, when the context supports it, is likely to lead to better results than you would get without it.

The Stakeholder Planning Process (SPP) is a way to plan. Believe it or not, a lot of commanders already use some form of that planning process. It doesn’t have to be woo-woo. It can simply be “teamwork” or “collaborative planning” or cleverly disguised as an opportunity to teach subordinates how to plan. SPP is a way to get The Quality Without a Name into your operations, but trying to us it itself without an organizational culture that supports it is useless. SPP only works inside a certain context.

You can’t just try to jump right into the SPP during a live training event, you have to train and prepare to use it. You have to make it the way that business is done in your organization, for almost everything. There will be times when you don’t have time to collaborate, or when you have to make a hard decision and take sole responsibility for it without allowing the group to shoulder that burden. But those times are the deliberate exceptions, not the way that business is done normally. The way you make decisions has to match your unique context, and sometimes allowing things to emerge naturally doesn’t make sense.

But when you allow your organization to collaborate and self-organize to solve problems, with your guidance and intent, it buys trust for you when you have to make hard decisions or quick decisions. When there is no trust, any decision the leader makes will be viewed as wrong or self-serving. When the climate of an organization deteriorates to the point where no one trusts any of the leader’s decisions, then the leader making sole decisions almost universally makes things worse. It doesn’t even matter if the decision is good if people feel like it was unfairly imposed upon them. This is why allowing progress to emerge through guided and managed interaction is so crucial because it builds trust between the leader and led. This trust buys flexibility for the organization when the leader needs everyone to shut up and do what they are told. And yes, those times always come eventually.

But leading by managing emergence rather than imposing orders on subordinates takes courage. You have to be willing to let people see who you are. As I discussed in the last essay (Simulacrum), you can’t just present the facade of what you want people to think of you. You have to be willing to throw out ideas and let them be judged by the group. You have to have confidence in your professional knowledge to be able to challenge others when they make suggestions that will lead to error. You have to have the strength of character to moderate a group of people who all have different ideas. And if you can’t do this, you have to find someone who can and support them. Fortunately, so many of the leaders I’ve had in the Army have been able to lead like this.

As an aside, the extremely high quality of leadership in the US Army is one of the things that has inspired me to continue to serve! But it’s the few poor leaders I’ve had from whom I have learned a great deal. But another remarkable thing to see is how those leaders have learned and grown throughout their careers.

Wrapping up

If you want to have a team that has The Quality With No Name, where people trust and support one another, where problems seem to be resolved instantaneously, and where people take accountability and ownership, it only comes through emergence. You cannot will it into existence. For The Quality Without a Name to emerge, you have to create an environment in which it can emerge. You do this by getting the right people together and guiding them as they work to solve the problem. And by doing this iteratively, over time The Quality Without a Name will emerge.

Where are we?

I’ve written 10 essays so far, with an average length of 4,000 words. They are all connected and mutually supporting and I’ve put in many hours thinking, reading and writing. If you are new to the newsletter, I highly encourage you to go to the archive and read the ones you haven’t read.

If you are a regular reader and have read all of them, I hope you can see how I have tried to weave an intricate picture of my thinking thus far.

Next week I am going to send a shorter newsletter to ALL subsccribers that will be an example of the type of newsletter that PAID subscribers can expect starting next year.

Should you upgrade to a paid subscritiption?

If you saw me at a bar, would you buy me a beer or would you just say, “thanks for the newsletters?” If you’d buy me a beer, then a paid subscription is for you. If you just want to say thanks, then I say, thank you for reading!

Thinking Fast and Slow pg. 53.

Midnights feels like Taylor used too much critical thinking. Those songs are not correct.

one of the most memorable classes I ever took was on the virtues of "managing by walking around". It was a case study of how feeling-driven leadership and fairly spontaneous presence could produce outcomes similar to, and in many instances better than, the traditional planned (i.e., critical thinking) approach to leadership.