Reaction

This one will ruffle some feathers.

If you’re in a rush, scroll down to “Epilogue - The EDRE” and just read that. It will take about 90 seconds. Please hit the like button.

Prologue — Bored

My Executive Officer held the door open for me and announced “Company Commander!” as my junior officers and NCOs leapt out of their chairs and stood at attention. I walked into the small conference room and I waited until I got to my chair before saying, “have a seat, let’s get started.”

My First Sergeant knew the drill. He and the XO had 30 minutes, not a second longer, to set the agenda for the day.

This was our daily 30-minute stand-up meeting, the only regular meeting I had in the company. No training meeting, no maintenance meeting1, no command and staff prep meeting. 30-minutes, once a day, every day.

I sat there in silence trying not to look too bored as the First Sergeant and XO reviewed tasks and requirements. Everyone knew that I didn’t care what we were doing that day. I made it known early in my command that I had very little interest in what the company did on a daily basis.

It was always a productive meeting and not a minute was wasted. No joking around, no banter, all business. If they were going to make the 30-minute time limit, they had a lot of ground to cover, and they had to do it quickly.

As soon as the XO and First Sergeant were done it was my turn.

I stood up, walked to the white board, and wrote, “Priority: __________” and “Release Time: __________”

“Okay team, what is the priority for today?”

The XO piped up, “communication equipment maintenance and readiness, sir. I need all radios, antennas, SKLs, and BFTs, cleaned, inventoried, and checked to make sure they are working. Then bring me all the deficiencies so we can report to battalion. That just came out yesterday in a battalion order.”

I said, “Great, that is the priority. It doesn’t mean it’s the only thing we’re doing today, it just means that we’re not doing anything else until that gets done. First Sergeant, what time are we going home?”

“1700, sir.”

“How about 1400?”

“Sir?!!!” The First Sergeant laughed and gave me a playful look of righteous indignation. “You’re going to get me fired!”

“Fine,” I acquiesced, “Soldiers need to be gone by 1530. Staff Sergeants and above stay until 1700.”

The First Sergeant put his head in his hands, pretending to be frustrated by my antics.

“Alright team, have a great day and do great things!”

We all stood, saluted, and sounded off with our motto, “Send Baker!”

Conventional Wisdom

Every commander of every unit I’ve served in has, at some point, said some version of the same thing: “We need to be looking ahead and get proactive about deconflicting and synchronizing events. I don’t want to be constantly reactive and only focus on 50-meter targets.” This is typically followed by a laundry list of new trackers that the staff needs to make, new meetings that will be held, or new SOPs that will have to be written.

Despite all the effort I have seen go into being proactive, units constantly feel like everything is last minute, like they are constantly reacting to the latest shiny object, all while they are desperately trying to plan ahead. In military units, it always feels like there is an enormous amount of organizational friction and lack of planning as last minute tasks and changes of plan wear down the moral of the Soldiers.

This is because optimizing for being proactive sets you up to be reactive, while optimizing for being reactive allows you to be proactive.

This principle is so counter-intuitive and so anathema to everything that is bred into military leaders from the day they begin training, that almost no leader I’ve talked to agrees with it. But how does being proactive work out most of the time? Leaders are typically frustrated because they put so much emphasis and so much effort into trying to plan for the future, only to have to change those plans because of something they didn’t foresee, or last-minute changes because of new requirements or shifts in the operational environment. This frustration trickles down to the Soldiers and wears on unit cohesion—it destroys mutual trust and degrades the trust Soldiers have in the institution.

The irony is that everyone knows that this is going to happen! Especially when planning combat operations, we know that the plan is going to have to change as soon as we get into contact with the enemy. It is a maxim of military operations that “no plan survives first contact with the enemy.”

Focus

Am I crazy? Am I actually saying never plan? Never look ahead? How can you get anything done?!

I am not saying don’t plan. If you are a company commander and you know that you have to conduct a training progression that includes Fireteam and Squad situational training exercises and live-fire exercises, then you know that you have to reserve the training areas for those things, and order ammunition, and submit safety paperwork, and do a bunch of other things to prepare. The requirement to use resources for training means that you must reserve those resources according to the deadlines established by regulation. Looking ahead is unavoidable—it something that must be done.

The question is where do you, as a military leader, want to place the focus of your organization. I am not saying you shouldn’t be proactive; you should be, and you must be. I am saying that you should focus on making your organization very good at being reactive.

Capacity

When I was stationed at Fort Carson, CO, I got my hair cut at Caveman Barbershop. Patti, the owner, was incredible. If you were a new customer or if you wanted to do something new with your hair, she would spend about five minutes playing with your hair and examining your scalp. She wanted to learn your hair. She would then spend about 25 minutes cutting it and getting it juuuuuuuusssst right. And when you came back, she remembered exactly what she needed to do. And she only charged $20 for a hair cut ($15 for military).

The problem is that the wait at her barbershop was about 2 hours. I would arrive at 6am on Saturday so that I could be first in line when she opened at 7am, although there were usually 3-4 people there ahead of me. Every time I was there, customers would walk in, see the line, and walk right back out. And every time I went, I told her “Patti, you need to be charging more. Your low prices are brining too many people in the door. This means that you are making your customers pay with their time and you are missing out on cash every time someone sees the line and walks out.” But Patti was stubborn, “I’ve been charging the same prices since I opened, and it wouldn’t be fair to start charging more now.”

The barber shop was always full, which meant that Patti was almost always running at 100% capacity utilization. If she doubled her prices, she might have run at 80% utilization, meaning she would have had fewer customers, but the increased revenue from each haircut would have more than compensated for the loss of customers.

In most areas of life and business, it is rarely advisable to operate at 100% utilization of capacity. In fact, as capacity utilization gets above certain thresholds, things move away from optimization, as we saw with Caveman Barbershop.

Another example is road usage. Roads are designed to get motor vehicles to and from their destination as quickly and safely as possible. But if roads are running at 100% capacity utilization, that means that there is so much traffic that no one can get anywhere safely or quickly.

In business school, my operations professor stressed on multiple occasions that 90% capacity utilization was almost always a danger. And these dangers do not expand linearly, they expand exponentially. If you graph this phenomenon with capacity utilization on the X-axis, and a key metric on the Y axis (for traffic it would be travel time), you will see that the line is mostly horizontal until you reach 80% utilization, then it starts to go up. Once you reach 90% utilization, the line starts to turn vertical.

In manufacturing, as soon as a factory gets close to 90% capacity utilization, efficiencies start to go away, and risk starts to compile. Lead times for new orders go up, equipment starts to wear down faster, labor costs can go up, inventory piles up faster and transportation costs increase, and if something goes wrong at any stage in the process then it can bring the entire factory to a standstill. As costs increase, economies of scale diminish as the cost per unit goes up. High capacity utilization also means that the factory can miss important opportunities if a new customer comes along and offers a lucrative contract.

High hospital bed utilization is another area of risk. As the doctor/nurse-to-patient ratio goes up, quality of care goes down and risk of mistakes goes up. And when a restaurant’s capacity gets too high, the kitchen takes longer, wait staff gets overloaded, and overall quality goes down. Not only do fewer customers wait for a table, but existing customers who have a bad experience are less likely to return.

Obviously, there are risks to under-utilization as well. But that risk is more about bleeding to death slowly, rather than hitting catastrophic risks that start to compound at 90% utilization.

Set Up to Fail

It is important to note that the problems and risks associated with having too high of a capacity utilization come from practical experience, not a priori assumptions about a domain. In theory, 100% capacity utilization should be fine. If everything worked perfectly and leaders had perfect information, then 100% capacity utilization would be a goal, and anything less would just be waste. It is only in the real world that we see, a posteriori, the risks associated with operating at maximum capacity.

But when some leaders see excess capacity not being used, there is a little voice in their head saying, “find something to do to use that excess!” In my essay “Focus” I recounted a true story from the book The Mythical Man-Month about a manager who chooses a large team for a job that should have been done by a small team because he felt that if he gave the job to the small team, then all the people on the large team would have nothing to do. In other words, he would have been wasting man-hours. But the result was disastrous, and it was apparent that the job should have been given to the small team.

When it comes to increasing capacity utilization in the military, it means using more and more time and organizational energy to try to accomplish more and more things. But as we spend more time with pre-planned activities and requirements, our ability to do the basic things correctly diminishes.

In the context of war, military leaders understand the importance of keeping a reserve. If a unit in battle is running at 100% capacity utilization, there is exactly ZERO flexibility for the commander because it means that all the available combat power is being used. 100% capacity utilization means that you are about to be overrun by the enemy. This is why commanders are so focused on controlling the commitment of their own reserve force, and on trying to trick the enemy commander into committing his reserve too early or to the wrong location. As soon as the reserve is committed, the commander’s options diminish to, essentially, zero.

But for some reason, we don’t carry this logic into garrison.

We know this because if you go look at any operational unit’s calendar, you will not see this precious thing we know as “white-space”—days or weeks where nothing is scheduled. Of course we have days off, but there are no, or very few, days where nothing is planned. This is because white space, like excess capacity, feels like waste. And waste, as we all know, is bad. So rather than keep excess capacity, some leader, at some echelon will fill those empty places on the calendar with something.

Sometimes leaders will place white space on the calendar. But as soon as the higher headquarters sees that a unit has white space, they fill it themselves with myriad other tasks. Because of this, some enterprising leaders will attempt to hide white space by placing large banner events that makes it look like they are busier than they are. When I was a company commander, for example, I knew that I could do my squad live-fire exercises in 3 days, but I blocked off the whole week. That bought me 2 days of white space. I was always trying to do little things like that to get as much excess as possible. And oh boy did it come in handy—not just for me, but for my entire battalion, as you will read about in the epilogue.

By constantly filling white space, by constantly looking for more and more things for soldiers to do, by constantly saying “yes” to the higher headquarters, we diminish our excess capacity and assume all of the inefficiencies, risk, and organizational friction associated with high capacity utilization. And by doing this, we are setting ourselves and units up for failure.

Mitigation

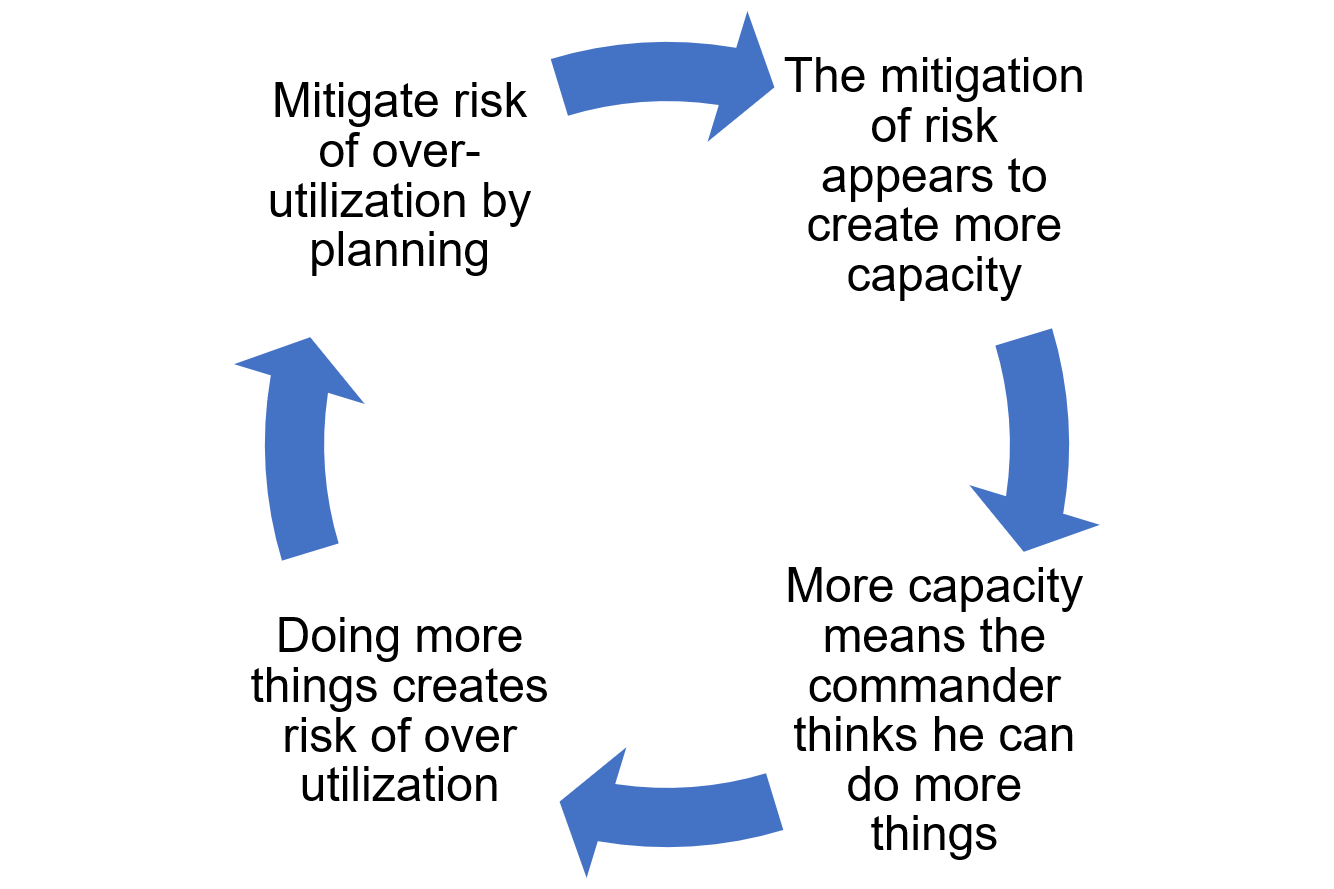

Leaders attempt to mitigate the risks associated with high capacity utilization by trying to project what will happen in the future. If only units could anticipate all of the things that the future holds, then they could perfectly plan for how to align manpower to tasks, and they could arrange events with maximum efficiency. But doing this also creates a feedback loop: if leaders believe they know the future, and can arrange resources and manpower with maximum efficiency, then they are able to do more things!

But leaders don’t know the future. Even in a garrison environment, where there is no enemy trying to actively thwart you, the best laid plans go awry. And when things don’t go according to plan, units are running at too high a capacity to be able to react smoothly. The junior enlisted Soldiers feel this more than anyone else. “Lack of predictability” is one of the most common complaints from Soldiers and their families in a garrison environment.

All of this stems from commanders’ desires to be proactive.

Being proactive means doing more things—using more and more capacity. And the more that capacity utilization goes up, the less able the unit is to react when things change or last-minute requirements are passed down from their higher headquarters.

Things always change! Especially in a garrison environment, things are constantly shifting. And units are always feeling overworked and under resourced, even if it doesn’t look like it on paper. being too proactive means not being able to react, and even small things break you.

Preparing to React

The story in the prologue was the story of how I prepared my company to react. I didn’t like to have detailed plans for every day or maximizing all the available time. And, as I said in the story, I made it known that what the company did on a daily basis was a trivial concern of mine. I didn’t even read the weekly orders that were published by the battalion (except on rare occasions)—my XO and First Sergeant did that. My First Sergeant, Brian Blow, had an extremely good task tracker that kept the company on track, and we consistently completed tasks ahead of all the other units and we were never delinquent on anything. We delivered. And our Soldiers were always the first ones to go home for the day.

But how could we deliver so consistently? Because, without even knowing what I was doing, I had built so much slack into the system, so much excess capacity, that when we got assigned tasks from higher headquarters, we could surge the entire company to accomplish them. Because we didn’t plan out every day or try to fill time gaps with “training,” we were always available to do stuff. If we were in garrison, the focus was doing garrison stuff—mostly administrative tasks and maintenance. Training was what the platoon leadership did as soon as all the garrison stuff was done. Serious training was reserved for the times we went to the field.

And when we were in the field we had zero distractions from things happening in garrison. When we were in the field we were in the field. The only thing we did in the field was train. And because we got all of our garrison work done in garrison, we didn’t lose training time trying to do garrison things in the field.

Because we were set up to react, we were never surprised. Because I never tried to guess what was going to happen, I was never disappointed. Our ability to react is what allowed us to be proactive about preparing for the expected—the things we were pretty sure were going to happen, like Combat Training Center rotations and major training events—and the things that we didn’t see coming, like the EDRE. Because we had so much excess capacity in our system, we were never jarred by changing circumstances. I could focus on planning major training events because I wasn’t distracted by what the company was doing on a daily basis.

I wasn’t focused on doing stuff. I was focused on preparing to do stuff.

For example, I knew that we were going to do a rotation at the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC), and that I had about 6 months before we left. In that situation, many commanders will start trying to do stuff to prepare because they think it will set them up for success. They will want to plan a whole bunch of specific training, write a company TACSOP, and do detailed plans for how containers are going to get packed, and what equipment they are going to take. They just do stuff because they think that’s what they’re supposed to do.

But sometimes I just did the opposite of what everyone else thought I was supposed to be doing. So, I didn’t do any of that other stuff that the other commanders were doing. Rather, I did as little as possible and made it known well in advance that as soon as we got close to JRTC that we were going to get really busy really fast. I was preparing the company to react when it was time to do stuff, rather than try to do a bunch of stuff to prepare, only to have everything changed at the last minute anyway. We didn’t do stuff, we did as little as possible while preparing to do stuff. We were preparing to react.

Epilogue — The EDRE

“Captain Caroe!” my radio-telephone operator (RTO) was yelling at me from the top of the range tower, “there is a radio call for you, sir”

I cupped my hands around my mouth and yelled back, “tell them it will have to wait, I am about to start the next iteration with this squad!”

My RTO leaned over the railing, gave me a more serious look, and said, “Sir, it’s Lethal 6 and he says it’s urgent, I recommend you come up here!”

Why was the battalion commander calling me on the radio? I scurried up the stairs, pushed open the door to the control room, picked up the hand-mic and said, “Lethal 6 this is Baker 6, over.”

After ten seconds of silence the radio came to life, “Baker 6 this is Lethal 6, I need you and your First Sergeant back at the headquarters building at 1830, over.”

“Yes, sir, I’ll get in my truck and head that head that way. Is everything okay?”

“Everything is fine, Baker 6, no one is hurt and no one is in trouble. We’ve got some late-breaking information and you both need to be here for a briefing.”

“Roger, sir, we’ll be there.”

“Lethal 6, out.”

My RTO overheard the radio call and asked, “what do you think is going on, sir?”

“I haven’t the foggiest, but if I start now I can get this last squad through before I leave.”

I sprinted down the stairs, ushered the final squad across the line of departure, and observed them as they shot down targets and maneuvered through the range. As soon as they were done and I had given them some feedback, Baker 7 and I jumped in a Humvee and drove to the Brigade HQ on the main post.

My First Sergeant and I walked into the decadent conference room at the headquarters building in full body armor and camouflage face paint. And if you couldn’t tell by looking at us that we had come straight from the field, you could certainly tell by the way we smelled.

We called the room to attention when the battalion commander walked in. He had everyone take their seats.

“Gentlemen we will be conducting an Emergency Deployment Readiness Exercise (EDRE). We don’t know where we are going or what we will be doing, but in two weeks we’ll be boarded on planes going somewhere. The only requirement is that we be complete with squad live-fire exercises.”

The commander of Alpha Company immediately jumped in, “sir, we aren’t scheduled to start squad live-fires until next week. How will we get all of our pack-out tasks done if the company is in the field?!”

The battalion commander turned to the S3 and said, “we are priority for all ranges and ammunition, we need to make sure that we meet the requirements.” The S3 was about to start issuing guidance when I raised my hand and said, “team, my company will be done with squad live-fire by first light tomorrow. If Alpha company just falls in on my training plan they can start getting their squads through this week”

They all looked at me with blank stares.

The battalion commander spoke first, “how are you already done? It’s only Wednesday. Aren’t you supposed to be out there all week?”

“Well sir, I planned for more time than I needed, and I can get three squads done every day. If they can have their first squads out there tomorrow, they can start running their squads through. This will give them more time to start packing up and getting ready.”

We agreed on a plan. Alpha company would fall in on my range the following day using my range safeties and my training parameters. The company commander would certify his squads and they would be ready for the EDRE.

I ran my squad live-fire exercise a little unconventionally. Rather than take the whole company to the range at once, as was standard, I only took them out a platoon at a time. As one platoon was finishing their last iterations, the next platoon would show up with their squads and the first platoon would go home. Because of this, I already had two platoons in garrison, with only one platoon in the field.

The two platoons in garrison started packing the next day while the other platoon came back and did their post-field-training tasks. By Friday the entire company had their equipment loaded in containers and we were knocking out all of the required pre-deployment tasks that had to get done.

Our excess capacity meant that we were always able to react. And if there is one thing I’ve learned in the military, it’s that the unit that reacts the quickest is the one with the advantage, not the one that tries to predict the future and plan for every little thing.

So, the next time that you hear someone talk about the importance of being “proactive” and “anticipating requirements” and “getting ahead of higher headquarters,” don’t lose focus on keeping your organization ready and able to react by maintaining as much excess capacity as you can get your hands on—with so many people trying to be proactive, you’re going to need it.

This was a light infantry company and maintenance was relatively straightforward and easy.

Thank you for this article. I am not from a military background but I wanted to share how relevant and useful these articles are in helping me build a highly operational business in the UK where planning, logistics and delivery are crucial. We have been doing our best to use mission command principles in our business and I strongly believe it has given us advantage over our competitors. Thank you

One lesson from my stint at the Pentagon was that “where you stand depends on where you sit” - I’m bending the original “definition” a bit to applaud the efforts to change one’s POV a bit from time to time because you can get better depth perception on your objective. I especially like the observation about what really is “peak” efficiency versus getting maximum usage out of your organization. It seems to me that one driver of the demand for 100% one hundred percent of the time is the notion as noted that unused capacity is waste rather than reserve. This is an attitude sometimes heard in businesses where the focus is on greatest return to the shareholders. For the uniformed services (and my home, the State Department), we have seen Congress label reserve capacity as “waste, fraud, and abuse”. One result is that neither Congress or industry was willing to foot the bill to support unused manufacturing facilities as a hedge against future demand because it was “waste” or “unrealized profit”.