If you are short on time, just read the first section below, it will take about 3 minutes. There is a poll at the bottom, please vote.

Wargame

When I was a company commander, I really liked my boss: the battalion commander. He was a really sharp guy: highly intelligent, very driven, very personable, and he looked the part of a military leader; tall, handsome, deep command voice, etc. He also had this great way of taking notes—he would start with a blank 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper, turn it landscape, and then write bullet points. And because they flowed logically from one point to the next, his notes were very easy to read when he passed them out.

When we were on the bus driving from Fort Carson, Colorado to the Joint Readiness Training Cetner (JRTC) at Fort Polk, Louisiana for a big wargame, I sat behind him as he wrote page after page of notes. He would write down a bullet point, think for about 5-10 minutes, and then write down another bullet point. He wrote about 10-15 pages of notes. I was impressed and I was really curious to know what was going on inside his head.

Once we got to JRTC the battalion commander distributed his notes to the staff and company commanders. The notes were about 90% focused on the staff; he had seen his company commanders in action, he knew he didn’t need to tell them how to run their companies. As I read through the notes, I began chuckling to myself because these notes were focused on very high-level tasks, and they would have been very hard things for the best staffs to accomplish. Our staff wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t the best in the world, either, and they needed a lot of work on the basics. Some of his notes included things like, “Develop intelligence collection matrices that utilize all available assets in such a way that it answers priority intelligence requirements and enables maneuver forces maximum reaction time,” and “Write operations orders that give maximum flexibility to maneuver companies while providing sufficient detail to ensure perfect deconfliction and synchronization.” I knew that if our staff focused on these high-level tasks, that they might struggle to just do the basics correctly.

My prediction turned out to be correct—the staff struggled mightily during the two-week long wargame. It was not the fault of any one individual, the staff simply was not properly designed and didn’t know where to focus its efforts to achieve the maximum benefit. It got so bad that at one point my radio calls to headquarters went unanswered for hours, and critical opportunities were lost. It wasn’t that communication systems had gone down, it was that the radios in the headquarters tent had dropped their encryption and stopped working, and no one noticed because the entire staff was dedicated to planning the next operation.

We got through the rotation, and it wasn’t a complete disaster, but there were obvious areas for improvement.

When we got back from JRTC, the battalion commander called me into his office and asked me how I thought JRTC went. I told him that I thought the main problem was that the wrong people were in the wrong positions. We had enormous amounts of talent in the staff, but they weren’t in the right jobs. I also told him that I thought he needed to reevaluate his approach to the staff. He was always a little shocked at how direct I was, but he asked me to elaborate.

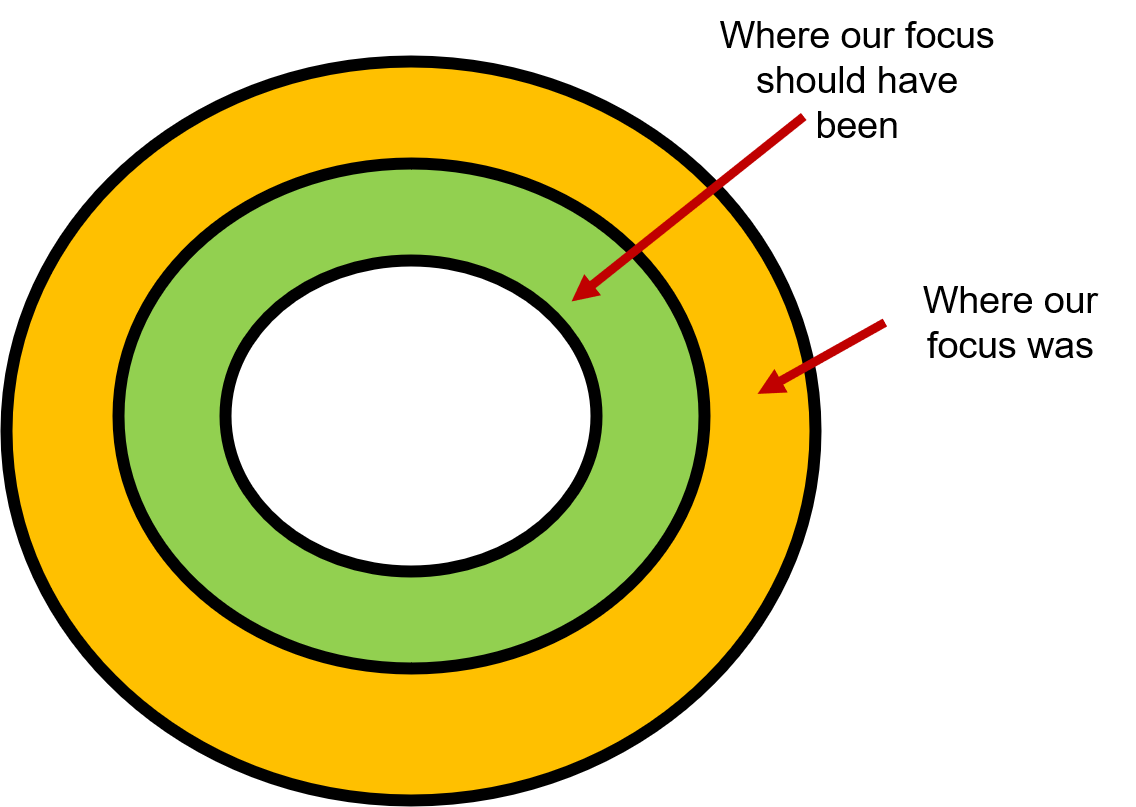

I used his notes from JRTC as an example. I went up to the whiteboard and I drew a circle. I said, “sir, the inside of this circle represents everything that a good staff can do.” I drew another larger circle around that circle and said, “inside of this circle is everything that a great staff can do.” I then drew another circle inside the “good circle” and said, “that represents what our staff could do prior to JRTC.”

He laughed and said, “yeah, or smaller than that! But I know what you are getting at, I know the staff needs a lot of work.” I said, “sir, do you remember the notes that you wrote and distributed at JRTC?” He said, “absolutely.” I looked at the white board and shaded in the area between the “good” circle” and the “great circle” in orange and said, “all of your notes fit in the orange shaded part.”

He laughed heartily and said, “well, I guess you’re right.”

I said, “sir, before you get the staff from good to great, you first have to get them to good.”

Perfectionism

I love telling this story because it illustrates a couple of things. First, my battalion commander was one of the best leaders I’ve ever had because he genuinely listened to me and wanted to hear my opinion on things. He was an intimidating guy, and I was one of the few people in his circle who would tell him exactly what I thought. Even when he told me he thought I was wrong, he made me feel heard, and I would have followed him anywhere. I had many other similar conversations with him where I told him exactly what I was thinking, and he never got angry or told me I was out of line.

The next thing it illustrates is that even great leaders can focus on the wrong things. Leaders, especially those with a perfectionist streak, have a tendency to want to make everything perfect. They assume the organization is already capable of doing the basics right and they start trying to accomplish great things. Great leaders can become so ambitious that they miss the point that their organization is not them, and doesn’t have the same level of skills. Just because certain leaders are thinking and capable of acting at a high level, does not mean that their organization is on the same page. My battalion commander was nothing short of brilliant, but he missed the fact that he was lucky if his staff wrote an order that was understandable consistent, and delivered on time, let alone able to balance flexibility and synchronization of effort.

But how then does a leader improve the organization? How do you get an organization to “good” so that someday you can take them to great?

High functioning leaders tend to focus on optimal organizational performance, so they place their focus on achieving high-level tasks. But oftentimes, organizations led by high functioning leaders are rarely at the level where they have mastered the most basic of tasks. When leaders ask their organizations to accomplish tasks above their skill level, it takes up an enormous level of organizational effort, and training basic tasks is subordinated, causing a further degradation in the organization’s capability.

It would be like taking a novice to the gym and telling them to squat an enormous amount of weight without further guidance. The novice doesn't know how to warm up properly so perhaps he does some static stretching instead of dynamic movements. Instead of putting an increasing amount of weight on the bar working up to the heavyweight after a few sets, he puts the full weight he was told to lift on the bar. When he shoulders the bar it’s in the improper position. As he squats down his back rounds and his knees collapse in as he strains to keep the bar on his shoulders. Perhaps our novice can go all the way down and then strain with everything in him to successfully squat the bar. Chances are, he’s going to injure himself, even if he successfully lifts the weight. And if he doesn’t hurt himself, he’ll be so sore the next day that he won’t be able to work out.

In an organizational context, disconnected leaders and, more importantly, their bosses, focus only on the result. The organization “lifted the weight” so to speak. Everyone thinks, “what a great job! Things must be going well in that organization.” Obviously, they miss the fact that the organization expended a lot of effort to achieve some short-term results while doing long term damage.

Organizations like this tend to erode as they are asked to do increasingly more difficult tasks. Status seeking leaders shift more and more of the burden onto subordinates as they attempt to squeeze every last bit of energy out of the organization before that leader hands the reins to the next leader. As the stress of the organization gets shifted to lower and lower echelons, misbehavior of all kinds begins to surface.

The classic example is Wells Fargo defrauding their customers. The leadership put immense pressure on managers to increase revenues, and this pressure was transferred to the lowest employees in the company. Eventually workers at lower echelons were simply committing fraud—they opened fake accounts for customers, ordered credit cards, charged fake fees, all to make it look as though there was progress when there was not. The executives never set out to defraud their customers, but they created an environment where poor behavior was incentivized. The worst part is that the executives never took personal accountability. They claimed it wasn’t the culture, just the actions of a few bad actors. Wrong! People act in accordance with their incentives. Leaders are responsible for ensuring that people are incentivized to perform in ethical ways and they are constantly vigilant to guard against unethical behavior.

So, we can see that focusing on achieving results, rather than on improving your organizational capacity can have negative consequences. But, organizations still have to accomplish tasks and get things done. How can leaders balance the need to improve their organizational capacity with the need to generate short term wins? The most important thing is narrowing the organization’s focus. If the focus is everywhere all the time nothing will ever get done.

So, I developed a little exercise to help leaders place their focus on specific tasks to improve their organizations—to meet them where they are and help them improve rather than trying to get them to achieve a myriad of tasks outside of their circle of competence.

The Technique

Before we go through the steps, it is important to note that techniques like this are not a panacea and may not work for everyone. The purpose of this task to ask, think about, and answer a few questions: What things can we do to improve the organization? Who is ultimately responsible for getting those things done? How will you measure completion of those things? What is the deadline for completion? I only ever did this exercise once with my infantry company, it wasn’t something we did regularly. Exercises like this that are done too regularly become rote and self-defeating. The novelty of the exercise is the powerful thing. I am not saying you can’t do it more than once, I am only saying don’t treat it like some kind of religious exercise.

Step 1: Gather the team.

This is a really critical step because you need to choose the right people to be in the room. If you are a small organization of 10-12 people, then you should probably include everybody. If you have around 100 people, like I had as a company commander, you will probably want 5-8 of your closest leaders, I had my platoon leaders and platoon sergeants. If you have a larger company with many departments and teams, you will want to train the managers on how to use this technique. This isn’t an exercise that C-Suite executives of large organizations should be doing in isolation—you need people in the room who understand the nitty-gritty details of everyday business and who are willing to give an honest assessment of the organization’s performance and potential.

Step 2: Assign Domains

What are the 3-4 main areas of your team organization? For my infantry company it was: 1) Training, 2) Administration, 3) Maintenance and property accountability, and 4) Morale. For a manufacturing enterprise it might be manufacturing process, sales, administrative and personnel systems, and supplier relations. For a sales team it could be lead generation, lead engagement, sales training, and sales tracking and administration. It can any number of areas. This exercise can scale to fit the size and scope of your organization. The point is to find a few areas that are broad enough to discuss, but focused enough that people can all have a similar vision of what that domain looks like. The domains should be things that almost everyone in the group can think about intelligently. They don’t have to be experts on each domain, but they should know about the domain in general and have an idea of how the company is operating in that domain.

Step 3: Depict the Domains on Bullseye Target

Everyone needs to be able to see the bullseye. You can use any number of rings. I’d recommend at least four and no more than 8. If you use 10 rings, then people naturally gravitate to 7, so avoid using 10 rings.

Step 4: Imagine the worst similar organization you can think of

Ask participants to take about 10 minutes to think about what the worst organization imaginable looks like in each of these domains. If you are a logistics company, imagine the worst possible logistics company. If you are a software provider, imagine the worst possible software provider in your sub-specialty. If you are a military unit, imagine the worst possible military unit of your type. This imaginary organization is completely failing at everything imaginable. What do they look like? Alternatively, you could say, “imagine our organization were the worst it could possibly be. Even if you think it is bad now, imagine the worst case scenario in each of these domains.” 10 minutes will feel like a long time, but people need to really think about and put pen to paper. And if people need more time, give the group as much time as it needs.

Step 5: Discuss the worst possible similar organization

Go around to each participant and have them read aloud what they wrote in each domain. Here is a brief example from my company:

Training: No training plan, unsafe training events, no train-the-trainer events, training not resourced, fail all tactical evaluations.

Maintenace: All equipment dead-lined, no maintenance paperwork, equipment is lost, and no accountability paperwork completed, no one cares about doing the small things correctly.

Administration: Awards and evaluations skipped or perpetually late, leave paperwork does not get signed or properly routed, no accurate phone roster of personnel, security clearance paperwork expiring consistently.

Morale and Discipline: No unit pride, high-risk behavior from soldiers, no sense of purpose, fraternization between soldiers and NCOs and officers, officers and NCOs being disrespected, hazing, no individual soldier discipline.

You will know that things are on track if most people’s comments are more-or-less the same. Everyone should have the same basic idea of what a failing sales team looks like. The point with this part of the exercise is get the group to imagine what failure looks like. It doesn’t matter what they say, as long as everyone has the same basic idea.

Step 6: Imagine the perfect similar organization

This is just the opposite of step 4. Imagine what perfection for your organization or a similar organization looks like in each domain. Take 10 minutes to think about it and write it down.

Step 7: Discuss the most perfect similar organization

Just like step 5. These should all be relatively consistent with each other. Feel free to jump in and encourage people to clarify and discuss. Make this whole thing as interactive as possible. If the leader or facilitator is doing most of the talking, you are doing it wrong.

Step 8: Determine where your organization is in each domain

The reason you ask people to imagine the best and worst possible organizations is so that you can compare your own organization to the same top and bottom baselines. If the worst possible organization is in ring #1 on the picture above, and the best possible organization is the bullseye in ring 6, ask people to rate where your organization is currently in each domain. This is usually done best if people vote secretly, and then the facilitator takes the average. You can also make this an open discussion, as long as people aren’t afraid to tell the facilitator that the company is in ring 1 in each of the four domains. It really doesn’t matter how you get to the number, or what the number is. Just make a mark on the diagram on whatever ring the group can agree on. If you spend 15 minutes arguing over whether the organization is in ring 3 or 4, then you are doing it wrong. Some discussion isn’t bad, but this process should be relatively quick.

it should look something like this:

Step 9: Ask the question and assign tasks

For each domain the question is not: how do we go from level 3 to level 6? You can’t move 3 levels. It’s impossible; that is too big of a leap. The question is: how do we go from level 3 to level 4 or even level 3.5? You can only move one level in each domain. The whole point of this exercise is action. If you generate a bunch of platitudes or overly generalized goals then you are doing it wrong. “Improve employee satisfaction by 10%” is too broad. You need a specific task, a measure of performance and a measure of effectiveness. This is the hardest part of the exercise.

Completing these tasks doesn’t have to move you up a level. The important thing is kaizen—continuous improvement. You keep asking, what is one thing we can do to get us closer to the next level in each domain. To emphasize again, the tasks need to be SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-bound. You can have more than one task per domain, but I definitely would not go with more than 3. And I would assign a priority to one task at a time. Not one task per domain, one task at a time. If a single domain is most important to the overall effort, assign that domain as the company priority. It is the one that everyone else must support and that will be first in priority for resources. You can work on multiple tasks simultaneously, but assign a priority to a domain or to a task.

Step 10: Follow up

Reconvene with the group or with each responsible person individually as necessary to ensure they are on track to complete their assigned task(s) on time. Do not get distracted and do not forget about the tasks. Stay focused and get them completed! Hold people responsible. If a person is listed as the responsible party, there is no blaming other people—that single person is responsible for getting that task done.

Caveats

This isn’t supposed to be a rigid exercise! There are probably thirty or forty different ways you could accomplish the same end-state. The point is to ask and answer some questions: What are the big things we do as an organization? What will it look like if we do those things really poorly? What will it look like if we do those things really well? How are we currently doing on those things? How can we get just a little bit better at each of the things we do?

Final Thoughts

If everything is humming along for you and your organization, then I would file this away and pull it out if you ever feel stuck or directionless. This exercise is great if you are feeling overwhelmed and don’t know where to start, or if you feel like you can’t make progress. It is also great if you just came into a leadership position, and you want to set some priorities. I came up with this near the end of command and I only ever did it once with my leaders. But I handed it over to the commander who replaced me so that he could follow-up on tasks and ensure they were accomplished.

If you have any feedback please reply to this email, leave a comment, or send me a message on Substack messenger.

I don’t think it’s possible to stress enough, the value of learning to correctly set (and execute) SMART goals. I also remember one of your previous posts on priorities and it might be prudent to put that link here now. One of the most valuable things I learned from you is that there can only be one priority at a time. When a leader embraces that truth it brings everything else into focus, and keeps the whole team from becoming overwhelmed.

Yes. And I like the bullseye process. I’ve been on teams where there was enough trust and communication for this to work. The hardest part to me, though, seems to be how to get to that level of trust where people actually do talk honestly.