“The most valuable commodity I know of is information”

-Gordon Gekko, Wall Street

Scroll down to “Summary” to read a one-paragraph ChatGPT summary of this post

Intro

Prediction markets are all the rage these days. Everyone is talking about them in relation to the presidential election. Here as an excerpt from the NYT DealBook newsletter a few days ago:

Nate Silver, the famed statistician and election predictor posted today in Substack Notes that his live model would likely not be powerful enough to outperform prediction markets.

But what is a “prediction market?”

I have been playing around with prediction markets for the last 6 years or so. In this essay I am going to explain what these markets are, how they work, and how they can help you become a better thinker.

Information as a commodity

Prediction markets help people answer hard questions about the future. The answers to these questions can help inform decision-making.

Let’s say you work in oil and gas, and you want to know what the average price for gas will be in the US during November. Imagine that having this information will help you make decisions about how to invest in upcoming projects, or it will help you do an analysis to inform someone who has to make the decision.

What would you do?

You could try to build a forecasting model for gas prices. You kinda learned about that in business school, so that might work. You could try to call a friend who works in oil and gas lobbying in DC and get their opinion about the direction of gas prices.

But are these really the best methods?

At the end of the day, you are really just guessing using whatever limited information you can get your hands on.

But prediction markets are a tool that allow you to determine the probability of things happening or not happening in the future.

What do they say about gas prices in November?

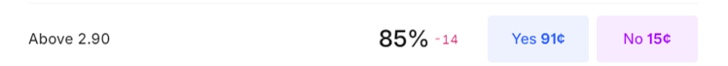

According to the latest trades, there is an 85% chance that gas prices will average above $2.90 and only an 11% chance that they will be above $3.20. So, you can determine with moderate to high confidence that gas prices will average between $2.90 and $3.20.

This is not a certainty, and you shouldn’t mortgage your house to bet on the idea that gas prices will fall in that range, but it gives you a decent idea of what the average price of gas in the US will be for November. If you had to have more precision, you could safely guess that they would be between $3.00 and $3.10.

But what is happening here? What are all the numbers? Where are these probabilities coming from? What are the blue and magenta buttons listed in cents? WHAT IS THIS?!

What is happening here?

Let’s put aside our imaginary oil and gas businessperson and dive into what a prediction market is.

The picture above is from a commodities futures exchange called Kalshi, which is a regulated financial exchange in New York City, USA. On the exchange, people are trading a financial instrument called an “Event Contract.”

Event Contracts can seem a little complicated at first, but once you learn a little bit about them and how they work you can begin to build some intuition, and they make a lot of sense.

Your purchase of an event contract is your vote about what is likely to happen in the future. If you vote correctly, the market will compensate you for being correct. If you vote incorrectly, the market will penalize you.

All prediction markets start with a question that needs to be answered. In this case, the question is: “Will the US average gas price be above $2.90 a gallon for November?”

Anyone can learn how these markets work. I PROMISE. But I can’t make you learn how they work. If you have no experience with this kind of thing, you have to put on your thinking cap, go slow, and concentrate.

Let’s look at the top line from the picture.

This line is an offer to buy a contract. Plain and simple.

The owner of this contract is entitled to receive $1 dollar if they provide accurate information about the average gas price in November.

What information are you providing?

You are providing information with your vote.

You can vote “yes” or you can vote “no” to the question of “Will the US average gas price be above $2.90 a gallon for November?”

You can choose the “yes” side of this contract or the “no” side of this contract.

If you choose “yes” then the contract will cost you 91 cents (the blue button).

If you think that the average price will be above $2.90, you can spend $0.91 to buy a contract that will pay you $1.00 if the average gas price is above $2.90.

If the average turns out to be higher than $2.90, then you will get back your $0.91, and a payment of $0.09 for being correct. The payment of 9 cents is how the market compensates you for providing accurate information about gas prices that others (like our imaginary oil and gas business person) can use to make decisions.

ALL PREDICTION MARKET CONTRACTS PAY $1.00 to the person who provides the correct information to the market. But you have to buy the contract.

If the contract costs 91 cents, that is an expensive contract, because you will only win 9 cents.

But if the contract costs only 9 cents, then it isn’t as expensive, and you can win the other 91 cents.

In this case, if the average price of gas for November is below $2.90, you will lose your original $0.91 cents as a penalty for providing inaccurate information to the market. You said that gas would be above $2.90 and you were wrong, so you lose your money.

But where does your 9-cent reward come from? And who gets your 91 cents if you provide the wrong information?

Your 9-cent reward came from the person who said that the average gas price would not be above $2.90. They paid at least 9 cents for a contract that would pay them a dollar if the average gas price was not above $2.90. And on the flip side, if they had been correct, they would have won your 91 cents.

But wait! How is that fair!? You had to put up 91 cents just to win their 9 cents, and they only had to put up 9 cents to win your 91 cents!? What the heck, man!?

Well, how confident are you in your prediction that gas prices will be above $2.90? If you are highly confident, then it makes perfect sense that you would be willing to risk 91 cents to win 9 cents. If you were pretty sure, but not that confident, then you have to ask yourself, “How much money am I willing to spend to buy this contract?”

After some thinking, you determine that you would be willing to spend 75 cents to win 25 cents. And if you can’t buy the contract for 75 cents, then you don’t want to buy it. Risking more than 75 cents to win 25 cents does not make sense to you.

When a lot of people participate in this market, you get a lot of votes about the average price of gas. Some of those votes will be informed, others will not be informed. The beauty of prediction markets is that they reward people who provide accurate information and penalize people who provide inaccurate information. And because you can buy as many contracts as are available in the market, you can match your level of confidence with the number of contracts you purchase, and what prices. So if there are 1,000 contracts available for sale at 91 cents, you can purchase as many or as few as you would like.

You may have noticed that the magenta button for the “no” vote does not cost 9 cents, but 15 cents. If my explanation is correct, then why does it say 15 cents and not 9 cents? I will explain that later, in the section called “Pricing Dynamics.” For now, just stick with me.

Why is prediction market information accurate?

Let’s imagine a professional gas analyst, let’s call her Susan, who does nothing but track oil and gas prices, and she has a deep professional understanding of where gas prices are headed.

She starts reading her normal reports and doing her price analysis and she realizes that gas prices in November are likely to tank to an average of around $2.50! She knows more about gas prices than almost anyone, and she is sure that the price is going to tank.

She logs in Kalshi to see what the market thinks about November gas prices and this is what she sees:

Quick note (I started writing this at night and picked up again in the morning and the market changed slightly. The contract that did cost 91 cents can now be bought for 95 cents).

Susan is seeing all the “no” contracts that are currently for sale (the prices in the red numbers). For 11 cents per contract, she can buy 400 contracts, which will cost her 44 dollars. She can buy 1,000 contracts for 12 cents, and another 1,000 contracts for 13 cents. She can also buy 68 contracts for 22 cents.

Susan would love to buy every single “no” contract she can get her hands on that costs less than 90 cents, because she is incredibly confident about gas prices and is willing to risk a lot of money to be compensated for being correct and bringing her information to the market. Susan wants to buy more contracts, but there are none for sale - she bought them all. So, she places a “limit” order for 10,000 contracts at 25 cents. This sends a big signal to the market essentially saying “HEY!! EVERYONE!!! I want to buy 10,000 “no” contracts for 25 cents a contract!!! PLEASE SELL THEM TO ME!!! Who wants my $2,500!?”

The market reacts to this immediately. The probability that gas prices average above $2.90 goes from 91% to 75%. This is because all of the contracts that were for sale below 25 cents have been purchased. The market is saying that if you want to buy a “no” vote, it is going to cost you 25 cents, not 11 cents. The market reacted to Susan’s information and “priced it in.”

This huge change in the market is seen by all the people who hold contracts. They see that a big player has entered the market, and that player seems highly confident that gas prices will not be above $2.90. All the market participants immediately start looking for new information. Some may start to slowly discover what Susan figured out. Those that do start selling their “yes” contracts for 75 cents and buying “no” contracts. The “yes” contracts get cheaper and cheaper because fewer and fewer people want to buy them.

The “no” contracts get more and more expensive because more and more people want to buy them.

The market flips in just a few hours or a few days. With the new information about gas prices fully priced into the market, it is now widely accepted that gas prices will likely be below $2.90.

That could happen.

Or….

Another analyst, Ajit, looks at the same information that Susan finds (but he doesn’t know about Susan or prediction markets). He writes an influential blog post about how gas prices are likely to stay consistent through November, and above $2.90. The blog post makes a very convincing argument with graphs and, you know, numbers and stuff.

Many market participants find this blog post and determine that the person who is buying the “yes” contracts is insane and mistaken, and they are more than happy to continue buying “yes” contracts.

The demand for “yes” and “no” contracts stabilizes until it is roughly equal. The “yes contracts continue to trade between 55 cents and 65 cents, while the “no contracts” trace between 35 cents and 65 cents. Susan does not have enough money to completely over-power the market.

What we see in this instance is that the market is uncertain about what the average gas price will be.

As the days go on and conditions change, traders on one side or the other will pull the market one way or another by increasing and decreasing their position sizes and overall outlook. As the end of the month nears, and there are fewer days during which the average can be affected, the market will move unrelentingly towards the correct side. At some point it becomes mathematically impossible for the average price per gallon to move below or above $2.90, and the market essentially falls quiet.

Prediction markets tend to be accurate because they put on a price on the answers to questions. If the price on “yes” goes up, it means that the available information supporting “yes” is growing, as is the confidence that traders have in that information. Because traders are rewarded for being correct, they are incentivized to vote accurately and base the size of their trade on their confidence. If they are highly confident, they will happily pay high prices. If they are moderately confident, they will refuse to pay high prices, but are likely to pay prices around 50 to 60 cents.

All the traders using all the available information and indicating their level of confidence with the size of their trades is what sets the price of the contracts, and that price represents the collectively established probability for the answer to the question. If “the market” (the collective trades of all participants) has priced a contract at 80 cents, it means that “the market” has determined that event has an 80% probability.

Pricing Dynamics

If contracts pay out 1 dollar to the winner, why don’t the “no” vote (the magenta button) and the “yes” vote (the blue button) always add up to a dollar?

To understand this, you need to understand “bids” and “asks.”

In the picture above, the left side is the “order book” for the “yes” side of the contract, and on the right is the “no” side of the order book.

The “bid prices are in green on the bottom half of the chart, and the “ask” prices are in red on the top half of the chart.

The “ask” price is the amount of money you pay if you want to buy a contract. It means that someone else has placed a sell “limit” order, and is telling the market, “hello, everyone. I have a ‘yes’ contract that I would like to sell for X price. If you want to buy that person’s contract, you have to pay the price they are asking (or wait for them to lower the price or for someone else to offer a lower price).

If you look at the red numbers on the left side, you can see that you can buy 1 “yes” contract for 93 cents. Someone is asking for 93 cents in exchange for a yes contract.

The “bid” price is the amount of money you receive if you want to sell a contract. It means that someone (or a bunch of people) has placed a buy “limit” order as is telling the market, “hello, everyone. I would like to buy “yes” contracts for 89 cents.

Here is the unspoken conversation between buyers and sellers:

Bid: I want contracts for 89 cents.

Ask: I’ll sell them to you for 93 cents.

Bid: 93 cents is too high! I’ll only pay 89.

Ask: 89 is too low, I want 93.

Bid: No way, I’m not paying that.

Ask: fine

Bid: fine

If that is the case, then the market will be stagnant until someone changes their mind, or another player comes into the market and either buys at the ask or sells at the bid.

Look at the picture again. It’s important to note that the Bid of one side of the contract plus the Ask on the opposite side of the contract is equal to 1, exactly. Red 93 plus green 7 equals 1, Green 89 plus red 11 equals one.

If someone sells their “no” contract at the bid for 7 cents (green numbers on the right side), it means that the remaining 93 cents left on the contract will go to the person trying to sell their contract.

Likewise, if someone buys the “yes” side of a contract at the ask for 93 cents, it means that there are 7 cents left to get to a dollar, and the “no” side of the contract goes to the person bidding 7 cents.

Every transaction must equal logically equal 1 dollar.

The prices you see on the colored buttons are the “ask” prices for both the “yes” vote and the “no” vote. That’s because most people want to know how much it will cost them to buy a contract. You don’t need to know the bid price unless you are trying to sell a contract. If you add the two ask prices together, you will get some number over $1. it could be 1 cent, it could be 30 cents. This number is known as “the spread.”

“The spread”

The difference between the bid price and ask price on the same side of a contract is known as the “bid-ask spread.” The spread will always equal the sum of the two ask prices on either side of a contract.

The important thing to know about spreads is that they are a measure of “liquidity” in the market. The “tighter” the spread, the more liquidity in the market. If the bid is price is 49 and the ask price is 50, the spread is 1, which is as tight as it can be. If the bid price is 30 and ask price is 60, the spread is 30, and the spread is really wide.

Let’s look at two current trades to understand this and what it means.

The US presidential election is today. As you may have heard, there are a lot of people buying contracts on who will win the election. Because there are 214 million dollars in contracts on the Kalshi exchange, and people are constantly buying and selling, the market is liquid, and so the spread is tight. You can easily buy and sell contracts because there are a lot of other people buying and selling contracts. The market moves very dynamically with buyers and sellers constantly pushing the price back and forth. Lots of buyers and sellers, lots of liquidity, tight spread.

But let’s look at an illiquid market.

Readers of the Distro may know that I am a big fan of Taylor Swift.

I currently hold the “no” side of contracts on the question, “Will Taylor Swift release Reputation Taylor’s Version in 2024?”

Obviously, the idea that she would release Rep TV this year is insane. Why would she overshadow TPD which she hopes will win big at the Grammy’s?

As it turns out, there are not a lot of buyers and sellers in this market. While the presidential race has over 200 million contracts, this market has only 20 thousand contracts.

As you can see here, the spread is 10, which is quite large. It means that there is a big difference between buyers and sellers. The sellers are asking for 44 cents, but the buyers don’t want to pay more than 44 cents. So, transactions only occur when someone changes their mind, or a new participant buys at the ask. In fact, transactions only occur in this market a few times per day. Whereas with the presidential election market, you are getting thousands of transactions a minute.

What’s the point?

First of all, prediction markets are really fun! They aren’t where you will make your fortune. They won’t pay for your kids’ college. They won’t help you get out of debt. They are for financially stable people who like to research, make educated guesses, and enjoy the thrill of trading the contracts.

Second, and more importantly, prediction markets help provide information where it either doesn’t exist or is really hard to come by.

But who even needs this information!? Why do these contracts exist at all!? What is the economic utility of this!?

Neighbor, there are 8 billion people on this planet. People need all kinds of information for all kinds of different things. Who knows why any of this information is important? And maybe some of the information isn’t that important. But you don’t what information is useful and what isn’t. A market exists because someone recommended Kalshi create it, or Kalshi saw demand somewhere else for a market and created one. The whole point is that prediction markets provide useful information that people can use in a wide variety of ways. Those ways will likely remain unknown.

Third, and finally, prediction markets help you to think about things from a probabilistic rather than a binary point of view. There is a book called “Thinking in Bets” which I haven’t read, but the title suggests that it supports this point of view. When someone makes a claim like, “if the person I dislike is elected, then bad things will happen!” you should ask them, “what is the probability that you are right?”

If they say “100%,” then you should simply ask, “would you like to bet $1,000 dollars against my 10 dollars? on it?”

This is a great rhetorical tool, because you don’t have to argue with them. You might even agree that they might be right. But you are forcing them to think about what their claim and to question their certainty.

ChatGPT Summary:

This piece explores prediction markets, a type of financial market where participants trade on outcomes of uncertain future events—essentially betting on probabilities. By buying "yes" or "no" contracts on questions like “Will gas prices average above $2.90 in November?” traders express their beliefs about future events and are rewarded for accurate predictions. These markets aggregate information from diverse participants, resulting in probabilities that reflect collective insights, often more accurately than individual forecasts. This makes prediction markets valuable tools for decision-makers, as they leverage broad expertise and incentives for accurate predictions to gauge probabilities on real-world issues, from commodity prices to elections.

I am experimenting with a new newsletter

I am starting a newsletter tentatively called “Prediction Markets Weekly” where I will analyze all kinds of prediction markets. I will likely end up charging a very high monthly fee to receive the newsletter, but if you are a Distro subscriber and you sign up before the end of November, you will receive it for free for as long as you want to receive it.

I am not sure how long this new newsletter will last, but if you are interested in joining me as I explore these new markets, I’d love to have you along for the journey!

Subscribe here:

It will ask you for a pledge, but don’t feel obligated to pledge any money, just get the free subscription.

Want to participate?

If you want to start trading in Prediction Markets, I recommend Kalshi to US Residents.

You can get a little boost by using this link:

kalshi.com/sign-up/?referral=b41db83f-10c1-4f2a-82cc-f743d5d03f30

(I think we both get 10 bucks if you sign up, but I am not exactly sure how it works)

Please read this important disclaimer:

The thoughts and opinions in this post are mine only. No one is paying me to make this post. I do not speak for Kalshi or any other institution or organization, public or private. This is not financial advice. I am not qualified to provide you with financial advice. Trading in prediction markets carries extraordinary risk, and you could lose your entire investment. If you are interested in trading in prediction markets, you should seek out professional advice. This post is for entertainment only and should not be used to make investment or financial decisions.