Wittgenstein's Windmills

Writings about uncertainty, complexity, history, leadership, and more!

Wittgenstein's Windmills

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Quick Bites

-When it comes to the government, never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity (Hanlon’s Razor). When it comes to the media, never attribute to stupidity that which is adequately explained by malice.

-If you want to hire a conformist, search for people who describe themselves as “contrarian.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Word Count: ~2,000

Read Time: 7 minutes

“If you use a ruler to measure a table, you may also be using the table to measure the ruler” -Nassim Taleb

This week I worked on a group project for a class called Business Forecasting. Our task was to develop a forecast for food consumption at a hospital in Southern India. The hospital was having problems making too much food and they wanted to develop a better system of forecasting demand.

When we examined the data we saw that there was almost no correlation between the occupancy of the hospital and the amount of food that was supposedly ordered. This was confusing to me, especially since the case stipulated that we were dealing only with the orders of the in-patients. How could there be no correlation between the number of people who needed to eat and the amount of food that was ordered?

Now, I don’t think the correlation would ever be perfect. Some patients need to fast before surgery, some patients might only drink coffee for breakfast, some patients might have their family bring them food, and some patients may be authorized extra servings for whatever medical reason. But over time we should expect that the number of in-patients is at least loosely correlated with the number of meals that are ordered.

It was on this point that my team and I disagreed. The data, they argued, clearly showed the opposite of my assertion: there was simply no correlation between occupancy and food orders.

My team was using the data to measure reality, I chose to use reality to measure the data. So, I went and looked at the data more closely.

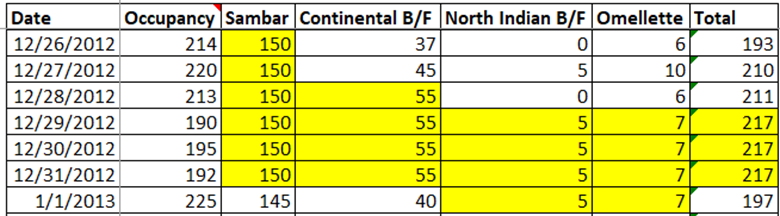

According to the case, the data we had in front of us was manually compiled from the order tickets submitted by patients every day for the last several months. Each order ticket listed different food items, and the patient would tick the box that corresponded with the food item that they wanted to order. Here is a sample of the data we were provided.

When I looked at the data, what I found was astonishing, and it became very clear why there appeared to be no correlation between occupancy and demand for food. When I looked at the most popular food item, “Sambar,” I discovered that almost every single entry ended in a 5 or a 0. I also noticed that there were multiple instances where the same number was entered multiple days in a row. At one point the data suggested that exactly 150 orders of Sambar were submitted 6 days in a row despite large changes in hospital occupancy.

Yes, there was clearly no correlation between occupancy and what the data was saying was the demand for food. But was it showing that there was no correlation because there was no correlation, or was it showing no correlation because the data gathered from the order tickets was unreliable? To me it was clear that the food data wasn’t reliable enough to make a forecast.

My argument to the team was that because the occupancy numbers seemed much more accurate, we should forecast occupancy, assume a correlation between occupancy and food demand, and then forecast food demand based on occupancy.

I provided them the following thought experiment:

If I am preparing to host a party at my house, how should I determine how much food to prepare? Should I ask, “how many people are coming?” Or should I ask, “how much food was eaten at my last party?” It was perfectly valid, I admitted, to use the amount of food eaten at the last party to decide how much food to prepare. But what if I told you that I was expecting a lot more people at this party, or a lot fewer? Should that have no bearing on my decision? According to the data we had, it didn’t matter how many people I was expecting at my party, it only mattered how much food was eaten at parties in the past.

To the team’s eternal credit they calmly explained and re-explained that the data didn’t show a correlation between occupancy and food demand and gave several reasons why that could be the case.

For the party example, imagine 50 people come to the first party but most people eat before they come, so not a lot of food is consumed. At the next party, only 40 people come but no one eats beforehand and so a lot more food is consumed. This demonstrates that the number of attendants and food consumption could be theoretically uncorrelated. It may seem counter-intuitive, they said, but there are a lot of reasons why hospital occupancy and demand would not be correlated.

The team was adamant that just because my intuition was telling me that occupancy should correlate to food demand does not mean that it must be the case. Our intuition, they argued, can often lead us astray. One team member who used to work for an airline gave an example of when he was analyzing data on lost baggage. His intuition told him that the number of lost bags reported to the airline should correlate with the number of bags the airline actually lost, but it didn’t. Sometimes the airline would have a lot of lost bags but few reports of lost bags, and other times they would have very little lost baggage but many reports of bags lost. There were, he found, a lot of factors at play.

Another team member gave an example from his work selling restaurant franchises. In that business, some food items in some regions correlated to occupancy, but many did not. In the Carolinas, pork sales were heavily correlated with occupancy, but in almost every restaurant around the country chicken consumption was constant regardless of occupancy.

In the case of the hospital, there could be a lot of factors influencing demand for food other than occupancy. It could be that food demand was heavily influenced by the number of patients from different castes, or maybe the type of patients in the hospital mattered more than the number of patients.

I agreed with the team in principle but pointed out that in their individual cases they were likely working with high-quality data. They could draw useful inferences from the data because the data was reliable and trustworthy. If we have intuition, we can test that intuition against the data only if we trust the data. But in this case, there was clearly something wrong with the food data. And because there was something wrong with the food data, we shouldn’t trust it to make a forecast and it wasn’t good enough to disprove our intuition. They saw risk in assuming a correlation between occupancy and demand, and I saw risk in using data that was highly suspect.

We spent 45 minutes arguing in the following circle:

Me: let’s forecast occupancy first, assume a correlation between occupancy and demand, and then base our forecast for food demand on occupancy.

Team: the data clearly show there is no correlation between occupancy and food demand. There are many valid reasons why this could be. We can’t assume occupancy is correlated to food demand.

Me: the data is bad. Look at these anomalies. We have random 0s entered for popular food items. Just because it shows no correlation doesn’t mean there is no correlation. It’s valid to assume that there is a correlation.

Team: we agree that the data stinks, but we have to use something to make a forecast. We are stuck with using this data, even if it has some problems.

Me: a forecast with bad data is useless. Since the occupancy data doesn’t appear to have problems, let’s forecast occupancy first and then base our forecast for food demand on occupancy.

Team: the data clearly show that there is no correlation between…

After several rounds of this, I stopped pressing the issue and they finished the assignment relatively quickly.

In Nassim Taleb’s book “Fooled by Randomness” he presents the concept of Wittgenstein’s Ruler. He writes, “unless you have confidence in the ruler’s reliability, if you use a ruler to measure a table you may also be using the table to measure the ruler. The less you trust the ruler’s reliability, the more information you are getting about the ruler and the less about the table.” My team and I could not come to an agreement on this issue because I was using the table to demonstrate the problems with the ruler and they were using the ruler to tell me the table isn’t the length that I thought it was.

From my point of view, it was unlikely that a dining room table was 53 feet long, and it was more likely that there was something wrong with the ruler. From my team’s point of view I couldn’t grasp that some people have really big tables! Maybe the table belongs to a king, or maybe it’s from Hogwarts.

“Data-driven” is a common buzzword these days. But a key problem is that data can be confusing and can often have multiple interpretations. If data is in the driver’s seat, you might feel like it’s driving you in circles. Oftentimes, data is used to support someone’s pre-drawn conclusions. Economist Ronald Coase (of “Coase Theorem” fame) said, “if you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything.” For example, during the recent blackouts in Texas, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal both used the exact same data from the Energy Information Administration to come to completely different conclusions about the role of wind energy in powering the Texas grid. It should come as no surprise that if you read both stories you get a much clearer picture of the situation than if you read only one. In fact, it would have been better to have read neither, and know nothing about the situation, than to read only one and get a distorted view.

The key thing that came out of our group discussion was an understanding of the risks of using the data that we had to make a decision about how much food to order. Would the decision-maker prefer to risk trusting a forecast that assumed an intuitive correlation that wasn’t supported by the data, or would they prefer the risk of using a forecast based on data that was highly suspect? The decision-maker could probably do worse than splitting the difference between the two forecasts, and then seeing which one performs better in the future. Or we could have presented only one model, not discussed the risks, and claimed that our forecast was “data-driven.”

I loved working with my team on this assignment, even if we came to completely different conclusions about how to do the forecast. From a pragmatic perspective, my team showed far more perspicacity than me. This was a relatively minor assignment in the grand scheme of the class and just accepting the data and making a forecast, as the professor asked us to do, was much easier than looking for more complicated alternatives. Moreover, we would have been putting our grade in jeopardy if we told the professor, “the data you gave us was unreliable, so we made some stretch assumptions.” In the end, it was a good intellectual exercise, and I believe my position was correct, but as a purely academic project, my aggressive application of Wittgenstein’s Ruler was somewhat quixotic. But who would I be if I didn’t seize an opportunity to spur Rocinante towards monstrous giants?

Thanks to my forecasting teammates PR, RH, and RS.

Have you ever come across an instance of Wittgenstein’s Ruler?

In this case which do you trust: the table or the ruler?

I’d love to hear from you! Just reply to this email and I’ll get back to you.

If you know of anyone who might like this newsletter, please forward it to them. If this email was forwarded to you please use this to subscribe.

From My Bookshelf

📚 Buy The Russian Revolution by Sean McMeekin

From My AirPods

🎧 Look for “@aecaroe” on Clubhouse. If you’re not on Clubhouse hit me up for an invite. I only have a handful of invites, so first come, first serve.

If you, or your team, are feeling stuck then check out my most recent YouTube video!