If you are short on time, skip to “You Old Fraud” and just read that. Please come back and read the rest later.

An Excellent Army Leader Development Program

Imagine an Army battalion that takes Leader Development very seriously. When the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Winchester1, first takes over command, he convenes a “Leader Development Working Group” (LDWG) comprised of the Battalion XO, S3, Command Sergeant Major, Operations Sergeant Major, and several others who he thinks will be able to contribute to the construction of a rigorous Leader Development Program (LDP).

At the first meeting of the LDWG the LTC Winchester issues his planning guidance:

Leader Development is very important to me, so we will conduct Leader Development every week on Thursday at 1630 in the battalion classroom. The audiece is Platoon Sergeants and above. I want our leader development program to be tied directly to our training calendar so that our leaders are getting the classes that they need to succeed on our training events. We will cover a new topic each week. Topics will be assigned to the companies or to a staff primary. Whoever is assigned a topic will teach a 45 minute class on the topic with a practical exercise followed by a 15 minute question and answer. Following that we will conduct an after-action review of the block of instruction so that we can continuosly improve the quality of the classes. The job of this working group is to analyze the training calendar and submit recommended topics to me for approval. Once I approve the topics we will publish the LDP schedule.

The commander’s guidance to the working group is very clear. After meeting several times over the next few weeks, the battalion Leader Development Program memo is published with notes from LTC Winchester. In the memo, the commander again makes it clear that Leader Development is very important to him. And because it is so important, he and the Command Sergeant Major will be conducting random inspections of the counseling packets for all NCOs and Officers to ensure that they are being counseled properly.

The memo gives specific parameters about what the counseling packets will contain, including a Battalion Leader Development Goal Sheet (BLDGS). On the sheet, the counseled soldier will conduct a self-assessment of their strengths and weaknesses, and submit short and long-term goals along with a plan of action to leverage their strengths and improve their weaknesses. Naturally, the BLDGS should be reviewed and updated once a quarter during periodic performance counseling. The memo makes it clear that this task is essential for the development of the battalion’s leaders, not simply an administrative drill. Leaders should view the BLDGS as a tool and an opportunity to develop personally and professionally.

According to the schedule, the first Leader Development Program class is an overview of the structure of Army Doctrine, going into the details of how manuals are numbered and the differences between an Army Doctrine Publication and an Army Techniques Publication. This is very sensible. Since all of the other classes for the Leader Development Program will be drawn from Army doctrine, it only makes sense that the Program should begin by going over the basics of doctrine.

The lieutenants from Alpha Company who are assigned to teach the class put in a lot of time and effort to ensure that LTC Winchester is pleased with their performance. Fortunately, they didn’t have to start from scratch — their company commander set them up for success by giving them refined guidance about what the class should entail and how they should focus their efforts. He even gave them a PowerPoint template.

The lieutenants put in several hours researching and building the slide deck before doing a practice run with the company commander. The commander gives them some very developmental feedback about the presentation, including the fact that using a uniform font and font size is a critical aspect of presentations. The lieutenants should also ensure that they speak up, but make sure not to yell at the audience. They should also not talk too fast, or too slow for that matter.

On the day of the class, the lieutenants do an absolutely magnificent job. They are eager, but not too eager; motivated, but not excessively so; knowledgeable, yet humble in their newly acquired knowledge. Their PowerPoint presentation has excellent graphics and uniform fonts throughout. At the end of the block of instruction, LTC Winchester, who arrived halfway through the class, congratulates them on their work. He hails the importance of the battalion Leader Development Program, declaring that it is crucial to the battalion’s success. Several of the other company commanders are quietly envious of Alpha company’s success and leave the class thinking of how they can ensure that their lieutenants surpass the standard left by Alpha company. In the coming weeks, much energy and organizational bandwidth will be dedicated to this endeavor.

Once everyone is dismissed, LTC Winchester asks the Bravo Company officers to stay back. He tells them to go to their offices and open up their counseling packets — they are the first company to be randomly inspected for compliance with the Leader Development Program guidance. They quickly get to their offices and open up their counseling packets. Upon inspection, LTC Winchester is very disappointed. Some of the required documentation is missing from the packets, including the BLDGS’s. LTC Winchester makes it clear to the Bravo Company commander, Captain Hall, that he is very disappointed. The BLDGS’s are a crucial aspect of leader development. How can the battalion become a lethal, mobile, agile, flexible, and empathetic unit unless its leaders are being properly developed?

The battalion commander takes solace in the fact that this was surely a failceeding moment. Hopefully, Captain Hall and all of Bravo Company’s officers can now see the importance of having an excellent Leader Development Program — the building block of any good battalion.

Once the battalion commander leaves, Captain Hall calls the lieutenants into her office to make a quick plan for updating the counseling packets. She is moderately stressed out because the company has some specialized training coming up for which she has been preparing for the last six months, and she doesn’t want the company to lose focus. She’s a good officer so she tells the lieutenants that the failure was her fault because she didn’t put enough emphasis on the counseling aspect of the program. She tells them that she is going to check the packets at the end of the following week and that they need to be updated, but that she wants them not to lose focus on the upcoming training. She asks the group if there are any questions.

Lieutenant Jones, sensing Captain Hall’s annoyance at having to deal with all of this, looks back and forth at the four other lieutenants with a confused look on his face and says, “uh, ma’am, can I ask a stupid question?” She sighs and says, “yes, what is it Jones?” In a somewhat sardonic tone, thinly disguised by a veneer of sincerity he asks, “uh, what does this have to do with, um, you know, fighting wars and stuff?”

CPT Hall is a loyal team player who supports the chain of command, so she explains the importance of leader development, and emphasizes that the program will help develop the battalion’s leaders.

One of the first things Jones learned in the Army was how to tell when a superior officer actually cared about something and when they were just saying the thing they were supposed to say. This was the latter.

Hal Moore

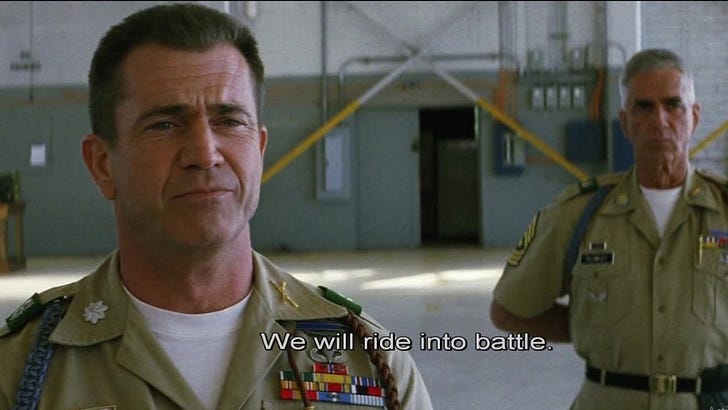

We Were Soldiers has always been one of my favorite movies. My favorite part is the beginning when we see Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore (played by Mel Gibson) personally training his officers. He leads them on ruck marches, gives speeches on runs, injects chaos into training events by “killing” key leaders.

Please watch this clip:

Hal Moore led the 1st Battalion of the 7th Cavalry Regiment in the Battle of Ia Drang in the Vietnam War. He is routinely held up as the example of an excellent military leader. In fact, as part of the leadership curriculum in the Command and General Staff Officer Course, students read a case study about Hal Moore written by none other than Lieutenant General (ret.) H.R. McMaster.

Compare what you see in the clip to my fictional story above. Do you notice a difference between Hal Moore’s approach and LTC Winchester’s approach?

Now, obviously, the case of LTC Winchester is a caricature. But, unfortunately, many Army leaders confuse good leader development with good-looking leader development. Hal Moore had a good leader development program by all accounts. LTC Winchester has a good-looking leader development program — good enough to show off to his boss, the brigade commander.

Many of my fellow officers have confirmed that they have been in units with highly formal programs where they felt totally under-developed, while others have been in units with no formal program and yet just being in the unit was the most developmental experience of their career.

Of course, you can have a program that both looks good and is good. When I was a company commander in the 4th Infantry Division, I was fortunate enough to have a battalion commander and a brigade commander who invested a lot of time into their leader development programs. In addition to having a formalized program for leader development, the battalion commander, LTC (now COL) Dennis would frequently come out to our company training and talk through our training goals and give suggestions. Just like LTC Moore, he would personally inject things into training scenarios for lieutenants to react to. He was a great example for all the officers, and we all looked up to him.

Likewise, my brigade commander, COL Zinn, would frequently gather the company commanders to teach us about a variety of things. During my company live-fire exercise he was right there with us the whole time and gave me excellent feedback. During my performance counseling, he demonstrated a level of insight that made a big impact on me. By having such excellent leaders to look up to, I have been more fortunate than many of my peers.

The point here is not that you, as a leader, shouldn’t formalize your leader development program. A formalized program with endstates, goals, benchmarks, etc. can be beneficial and sometimes might even be necessary. The point is that having a formalized program for leader development should not be confused with actual leader development. It is an addition to, not a substitute for, holistic leader development.

You can plan the greatest leader development program in the world, but it will all be for naught if you don’t first create a functional organization in which the leaders you are developing can thrive.

It is to this point that we turn next.

How to Grow a Carrot

Imagine if your friend came to you and said “I am trying to grow carrots, but I can’t them to grow. I plant the seeds carefully, I give them just the right amount of water, I make sure that the area gets enough sun but not too much, and it’s the right time of year for planting carrots. But I can’t them to grow! And I feel like an idiot because carrots are supposed to be pretty easy. I am starting to think that there is something wrong with the seeds.”

Although you don’t know much about gardening, you offer to come over and take a look—your friend is quite distressed about this carrot catastrophe and you are eager to help ease his suffering in any way that you can. He shows you the packets of carrot seeds while insisting that he thinks there might be something wrong with them. He says, “I’ve done everything to for these seeds. I swear I’ve given them just enough water and sun, they must be defective.” You ask him to take you to the garden to see where he has been planting them.

Upon inspection of the carrot growing area, you are quite confused. Of all the places that your friend could grow carrots, he has chosen what appears to be a child’s sandbox. But again, you don’t know much about gardening and your friend seems to have done some research, so you don’t want to be too direct in inquiring about the sand for fear of embarrassing yourself. You stand inquisitively over the sandbox pinching your chin with your thumb and forefinger. After a minute or so you say, “hmmm…I wonder. Tell me about this sand. Is this, you know, the best soil for carrots?” Your friend states flatly, “I read that carrots grow best in sandy soil, and this was the most expensive sand I could find, so I assume that it’s at least good enough. Good seeds should be able to grow here.”

At this point, you are quite sure that your friend has made an error by confusing “sandy soil” with straight sand.

You politely suggest to your friend that he dump out the sand and replace it with some dark soil. “It might not be a problem with the seeds,” you propose, “it might just be that they are having some trouble growing in sand. I know you are really focused on making the seeds grow by tending to them very closely, but if you just put them in different soil, they might start to sprout.

Just like growing carrots, developing leaders is more about creating an organization where they can naturally flourish without you having to do too much. If you are obsessing over the things you are doing to develop your leaders and not paying enough attention to the proper functioning of your organization, you are focused too much on the seeds and not enough on the soil.

The most important step in developing your leaders is to make your organization function properly. This may seem obvious, but it is an important point that is often overlooked. Bluntly speaking, who the hell are you to develop leaders if your leadership skills aren’t resulting in a functional organization? You wouldn’t take nutrition advice from someone who is super unhealthy, and you wouldn’t take financial advice from someone up to their eyeballs in debt, so why would anyone take leadership advice from someone who hasn’t demonstrated enormous competence in leadership by creating an organization that functions at a high level in all of its various activities.

The difficulty, then, lies in creating a properly functioning organization in which to develop leaders. But a functioning organization cannot be created by one person alone, it takes the work of many dedicated and competent leaders; and If the purpose of a leader development program is to develop leaders to be more competent, then this is paradoxical — it takes a functioning organization to develop competent leaders, and it takes competent leaders to create a functioning organization. Stated another way You cannot properly develop leaders without a properly functioning organization, and you cannot have a properly functioning organization without developing leaders. This seems like a classic Chicken-Or-The-Egg problem.

Resolving this paradox reveals a key point: developing leaders and creating a properly functioning organization are not two different things. They are extensions of one another. They are like M.C. Escher’s Drawing Hands.

When you take over an organization and you want to make it function properly and steadily improve, one of your first steps should be to identify and leverage the strengths of your key leaders and minimize the deletrorious effect of their weaknesses. Is doing this leader development or creating a properly functioning organization? The answer of course is: yes! This is why many people report that they feel the most developed as leaders when they are in really good organizations that function at a high level, even if there is no formal or structured leader development program.

As the leader takes more actions to improve the organization that aren’t directly tied to working through her subordinate leaders, she still develops her leaders by consistently showing what she is doing and how she is doing it, and what decisions she is making and why. She also gives her subordinate leaders the oppurtunity to provide feedback and the flexiblity to make decisions of their own based on her broad intent. If this sounds like creating shared understanding, giving commander’s intent, and building teams through mutual trust, and encouraging subordinates to take disciplined initiative, we can see that Mission Command, Leader Development, and creating a properly functioning organization are not three different concepts that can be separated from one another. They are all members of the same family. They share common genetics.

If a leader takes charge of an organization that is in serious need of improvement, their first priority should be to not make it worse. But to get the organization to improve over time, the leader has to work with the raw material that she has. Sometimes this means removing some people from their positions or moving them into a position for which they are better suited, promoting others, or bringing in some people from outside the organization. It means maximizing the strengths of your key leaders and minimizing the deleterious effects of their weaknesses. Helping people understand their strengths and then using their strengths to improve the organization develops leaders and creates a properly functioning organization. This process creates a feedback loop. As the organization improves it creates breathing room for the leader to spend more time identifying talent and expanding the scope and scale of the responsibilities of leaders in the organization (developing leaders), which in turn improves the organization.

(Thanks to RD for listening to me rant until I verbalized what became this section of the essay).

You Old Fraud

One of my favorite seasons of House M.D. is when Dr. House’s diagnostic team quits and Cuddy, his boss, makes him hire a new team. Over several episodes, he runs a hilarious survivor-style selection process where he begins with a large group of aspiring doctors and eliminates contestants every episode for mostly arbitrary reasons.

One of the characters trying out for House’s team was a doctor who was out of place because he was much older than everyone else, including House himself. Through several episodes, we see that this older doctor often has excellent insight into the patients that come into the care of Dr. House and his team. But in one scene, the old doctor is about to perform a minor procedure on a patient when he stops and hands the equipment over to another, much younger doctor, and says, “I’ve done a thousand of these, you could use the practice.” House sees this and is immediately suspicious.

At the end of the episode, we find out that this old doctor is not a doctor at all. He was a university administrator who audited all of the medical school classes multiple times over 30 years but had never done any of the hands-on training or done a residency. This was why he was unable to perform the most routine of medical procedures. He knew a lot about medicine, but he couldn’t practice medicine because he had never learned. House initially decides to keep him on the team as a “consultant,” but eventually fires him, admiringly calling him “a ridiculously old fraud.” House didn’t fire him because of any deficiency of knowledge — the old man was correct in his diagnoses most of the time. House fired him because he was simply a replication of the things that House already knew, and consistently said the things that House was already thinking — he added nothing to the team. House didn’t need more knowledge. He needed practitioners who were willing to use their judgment and clinical intuition to disagree with him. Medicine isn’t abstract. It is a real-world practice conducted with real-world consequences.

The same is true of leadership. It isn’t a purely intellectual exercise, it requires the ability to influence people in the real world to work together to get results. You can’t just read a bunch of theories and learn a bunch of models and then jump right into doing brain surgery. You actually have to practice leadership. Just as in medical school, the classroom is only a starting point.

I am told that the general pedagogical method for training doctors in medical schools is, “watch one, do one, teach one.” The best leader development tends to follow this same pedagogical approach. The best leaders have a leader development program that looks something like this:

WATCH me as I create a functional organization and explain to you what I am doing and how I am doing it.

DO as I do to create a functional organization of your own inside of the larger organization. I will watch you and give you feedback.

TEACH others what you are doing to create a functional organization and how you are doing it.

A lot of strong leaders don’t even put thought into this process, it’s simply a natural extension of their leadership skills. This isn’t a template or a model for leader development. How could it be? You can’t just follow this model. It’s highly contextual depending on your organization and your mission. The point here, which I continue to emphasize, is that the most effective leader development occurs within the context of a functioning organization, and one of the hallmarks of a properly functioning organization is leader development.

The classroom can be an effective tool for leader Education, but it plays only a minor supporting role in leader Development. This is a confusion we will explore in the next section.

Education v. Development

Leader Development and leader Education are not the same things. To quote Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction, “it ain’t even the same f*cking sport.”

Leader Development, as we discussed in the previous section, is inseparable from making your organization function properly. But when we think about leader “development” in the Army, the images that come to many people’s minds is LTC Winchester’s program — PowerPoint, Army doctrine, vignettes, counseling packets, and maybe even a book discussion. But are you really developing leaders in a classroom, or are you educating people who are in leadership positions? Much of what we call “leader development” in the Army is really just “leader education.”

Just to make sure I don’t overstate the case, leader education is really important. If a battalion is getting ready to go to the field to train on Movement to Contact, it makes perfect sense that they would spend some time in the classroom talking about Movement to Contact doctrine. If I were a battalion commander, my style would be to teach the class personally, but I recognize that personally teaching a class isn’t every commander’s style. I could go off on a rant about why lieutenants shouldn’t teach classes to other lieutenants, but I’ll save that for another time. The point here is that it often makes sense to educate your leaders, and a classroom plays a key role in that.

But educating your leaders in Army doctrine, military history, or anything else, plays only a small part in leader development. You can educate your leaders all you want in these topics and you can still have a poorly functioning organization in which leaders feel underdeveloped. In fact, mandatory classroom instruction which is done in the context of a poorly functioning organization is probably detrimental in the extreme. Leaders won’t take it seriously, they won’t concentrate, they won’t engage (except maybe to show-off), and they certainly won’t develop as leaders. These tedious classes erode the credibility of the organization and damage morale.

Leaders are developed in the context of a properly functioning organization because leadership is an applied skill that occurs in complex, dynamic, and uncertain environments. You can’t just hand someone a bunch of leadership models based on academic theory, slap them on the butt and say, “Have fun storming the castle!”

If you teach someone a leadership model, you first have to demonstrate how you use it effectively and then set up an infrastructure that allows them to implement it and get feedback. For example, here is a class that I taught to my squad leaders when I was a company commander. (It should already be cued up to 29:08).

I am saying: “Here is a concept that I want you to consider. This is how apply it every day. You can apply it too.”

Definitions

The learned scholars who comprise my readership may have noticed that I haven’t really defined any of the terms that I use repeatedly, most obviously: “Leader Development” and “Properly Functioning Organization.” And if I give what appears to be a definition for a term in one section, I might use the term in violation of the definition in another section, creating what appears to be a contradiction. This lack of structure is purposeful. These ideas are meant to be as dynamic as the environments in which they are meant to be applied. They are vague, general, and shape-shifting by design.

This newsletter is my artistic expression. It’s meant for you to enjoy, interact with, and play with. It has brought me immense joy to hear from so many of you that you have found what I have written so far to be insightful and helpful. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoy writing it! If so, please consider sharing it on your social media platform or forwarding it to a friend. The goal is to write a book someday and having a developed and engaged audience makes that dream significantly more tangible.

Next Month

In part one of this essay (last month), I argued that leader development efforts that are focused on improving weaknesses in individual leaders can harm the organization and often don’t help the people they are trying to help. It is much better for the organization if you, as the leader, identify the strengths and weaknesses of your subordinate leaders and focus almost exclusively on maximizing their strengths. Doing this will increase the effectiveness of your organization and do a better job of developing your leaders.

In this essay, I explore different ideas about how we think about leader development in the Army. I propose that the best leader development happens within the context of a properly functioning organization, and that an organization functions properly by developing leaders.

In the next essay, I am going to explore different themes related to ethics training. If you haven’t read my essay Certitude, the essay will be in that same vain but go into much more depth.

This is an entirely fictional person. If there is a real LTC Winchester out there, this character is not that person.

You make a good point about good leadership versus good looking leadership. The best leader development will always be experience itself in my book. Also, BG Zinn.

Great article. I will have to find the time to chat about your definitions.

I think the biggest challenge in leader development is to encourage self-development. Excellent leaders are ones that never stop learning. I was lucky enough to create the "coffee and Clausewitz"

method of encouraging peer-learning and self-development just by being around a remarkable group of Soldiers. Ultimately, I believe the mark of a truly successful development program is it can "pack the house" when being entirely voluntary. https://thearmyleader.co.uk/coffee-and-clausewitz/